By Kevin Cosby

Imagine contracting a buzzard as a real estate speculator to give you an assessment on a piece of property you are interested in purchasing. The buzzard flies over the property, does an investigation, and submits a report on the property. The report contains only one sentence: “The property in question has a lot of dead rabbits.”

You pass on buying the property based on the report and someone else buys the land. You later find out that the buzzard was right, but his report left out some significant details. There were a lot of dead rabbits, but there were also rolling hills, picturesque lakes, and beautiful flowers peeking through carpets of green grass.

The problem with the buzzard’s conclusion was that the bird could only see what it had been programmed to see. Canadian literary critic Robert Davies once said, “The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to see.”

Like the buzzard, we human beings are astonishingly disposed to missing what is obvious to the eye. When we look but fail to see, or we fail to see stimuli in plain sight, psychologists call this phenomenon “perceptual” or “inattentional” blindness. When you’re programmed to look only for dead rabbits, you miss all the other things going on in the scenario.

The recent stop of my wife and I by Louisville police officers is a real-life example of this truth. On Saturday, Sept. 15, around 10 p.m., Barnetta and I were headed home from a dinner date with two friends who had presented at the National Angela Project conference hosted by St. Stephen Baptist Church. We drove down Jefferson to Market Street and then turned left on 22nd Street, which is a one-way street going south. Several blocks later we turned right, headed west on Muhammad Ali Boulevard.

As soon as I made that right turn, the blue lights of two police cars were flashing behind us, signaling us to pull over. Immediately, what crossed my mind was, ‘Why am I being stopped, and by two squad cars, no less’? I knew I was not speeding, nor had I run the stop sign when I turned onto 22nd Street. I knew that I had turned right on Muhammad Ali while the light was green. I knew that even if the light had been red, I could have made a legal right turn onto the street after stopping.

Before the policeman reached my car window, I already had compiled a punch list of possible infractions to warrant the stop and mentally crossed each of them off. I could not figure out what I had done wrong.

When the officer approached me, instead of identifying himself and explaining the reason(s) why I had been pulled over, he created more uncertainty. After telling me to keep my hands where he could see them, he asked my wife and I, “What are y’all getting’ into tonight?” I thought, ‘Hopefully, the bed,’ because I had five sermons to deliver the following day.

The officer’s question wasn’t meant to be disarming or friendly; rather, it had an accusatory tone. My wife and I both interpreted his question to infer that we were engaging in something criminal or nefarious. At the time, I wondered if he thought I was a suburban resident driving an expensive European car who had ventured to the West End looking for a prostitute or drugs.

My hypothesis was further validated after he asked both Barnetta and I for identification. I knew that it is not customary police procedure to ask a passenger for ID on a routine traffic stop. I could only conclude the officer suspected that my wife and I were doing something illegal. While the officer queried me, the officer from the second squad car had stationed himself at the passenger’s window and was peering down at my wife with his flashlight shining. Additionally, a plain-clothes officer stood in the distance watching the entire episode unfold. Our vehicle was under the guarded eyes of three law enforcement officers, yet I still had no idea what I had done wrong.

At this point, I processed anything the officer asked me as an interrogation to prove criminality. The officer, noting the Simmons College of Kentucky insignia on the shirt I was wearing, asked me what was Simmons College. I felt insulted and humiliated by his question about Simmons. Can you imagine a police officer asking what’s U of L? What’s Spalding? What’s Bellarmine? It’s not like Simmons only recently opened. The college was founded in 1879 by former slaves. Simmons is the only private black college in the commonwealth, and the only college located in west Louisville, the area that the officer was policing.

It was not until he asked the insensitive question about Simmons that I identified myself by name and informed him that I am the president of Simmons and senior pastor of St. Stephen Baptist Church. Although he now knows who I am, he still does not identify himself or give a reason for the stop.

I asked him whether it was necessary for him to see my wife’s license; he confirmed that it was not necessary. However, he stressed that I had to give him my license. My wife voluntarily gave him her license. She wanted to verify that she was my wife, so that he would not think that she was a prostitute or some random woman I had picked up.

In our later discussion about the incident, Barnetta shared with me that she didn’t want it reported that I was in my car with an unnamed woman who refused to give her identification to the officer.

After the officer returned to his squad car with my license, I deemed it wise to pull out my phone to record the remainder of the encounter. A few minutes later, the police officer returned to my car window and said, “Everything checks out. This is your car and you do have insurance.”

The officer still had not identified himself nor told me what I had done to be detained. He told me that we were free to go.

It was then that both Barnetta and I asked him what I had done to warrant a traffic stop. Only then did he tell me that I had made an “improper turn” on an unspecified street. He did not define what the improper turn was. He also said that the license plate frame around my license tag from the dealership is illegal.

He said, “I am going to give you a warning this time,” and with that I was free to go.

Many people who have read about the incident have accused my wife and I of acting like victims and making false claims of racial profiling. District Maj. Eric Johnson has said, “Rev. Cosby isn’t immune from traffic violations.” And to this I say, “Amen!” Like most citizens who live in west Louisville, I am not asking for preferential treatment.

But we do, however, want to be free from prejudicial treatment.

No one should be above the law, but all citizens have a right to expect equal protection under the law. The way citizens are treated in one area should be the same way they are treated in other areas — regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, religion or socioeconomic status.

The protocol for a moving violation traffic stop is for the police officer to first introduce himself or herself and then tell the driver why he or she was pulled over. Then the officer is to ask for the driver’s license and proof of insurance. Nowhere in the Louisville Metro Police Department’s procedural manual does it instruct an officer to initiate dialogue with, “What are y’all getting’ into tonight?”

Proper protocol does not entail saying, “Let me see both of your license,” and attending both sides of the vehicle merely because the driver made an undefined improper turn and had a license tag frame that even the fraternal order of police sells on their website!

I am a firm supporter of our police officers; they lay their lives on the line for our safety each and every day. Jesus said in John 15:13 that there is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for another. In supporting our officers, I also issue this appeal: Don’t treat a person like a criminal over a routine traffic stop and then wonder why a black person might conclude he has been racially profiled.

The subsequent conversation around this event revealed to me just how much many in our community see the world like the buzzard. Some cannot perceive of a police officer making a mistake or making a biased judgment call. Many automatically are programmed to see only good in the police and victimology in black men.

Like the buzzard, we are all wired toward what we have been conditioned to see. Implicit bias against blacks is real and implicit bias favoring the police is equally real.

The Bible says in Jeremiah 17:9, “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: Who can know it?” That’s the Bible’s way of saying that most prejudiced and biased people have deceived themselves into believing they are impartial. Or, as James Baldwin once said, “You can’t fix a problem if you don’t face the problem.”

The issue of police bias must be faced so that it can be addressed. I’m not so naïve to think that every person’s voice will be heard like Kevin Cosby’s. And because I know that I have been given this voice, I am compelled to speak for those who will never be heard.

Since the police department has an internal investigation to review incidences of improper police behavior, I decided it was my duty to engage my right as a taxpaying citizen of Louisville to seek further investigation of the matter for the sake of those who do not know their rights.

I did not allow the video of the incident to be posted online to draw attention to myself, or to condemn and embarrass the police department. I did it to garner empathy for the many blacks in West Louisville who routinely and anonymously receive this kind of disregard at the hands of law enforcement. And as a result of sharing this episode, St. Stephen has been flooded with calls from people who have had similar encounters with police officers.

By sharing the video publicly, it is my hope that our city’s officers are more empathetic and compassionate toward all citizens. In addition, I want people, especially African Americans, to see an appropriate and safe response to law enforcement officers, even when you feel you have been falsely accused. At no time did my wife and I show disrespect to the officer’s authority. We respectfully and patiently complied with everything he told us to do.

My elders taught me long ago, as a young black man, that if I am ever stopped by the police to always be respectful and cooperative. “I can get you out of jail,” they said, “but not out of the cemetery.”

It is my sincere hope that this video will motivate the police department to establish a standard, universal policy for engaging citizens during routine traffic stops. No one should be asked, “What y’all gettin’ into tonight?”

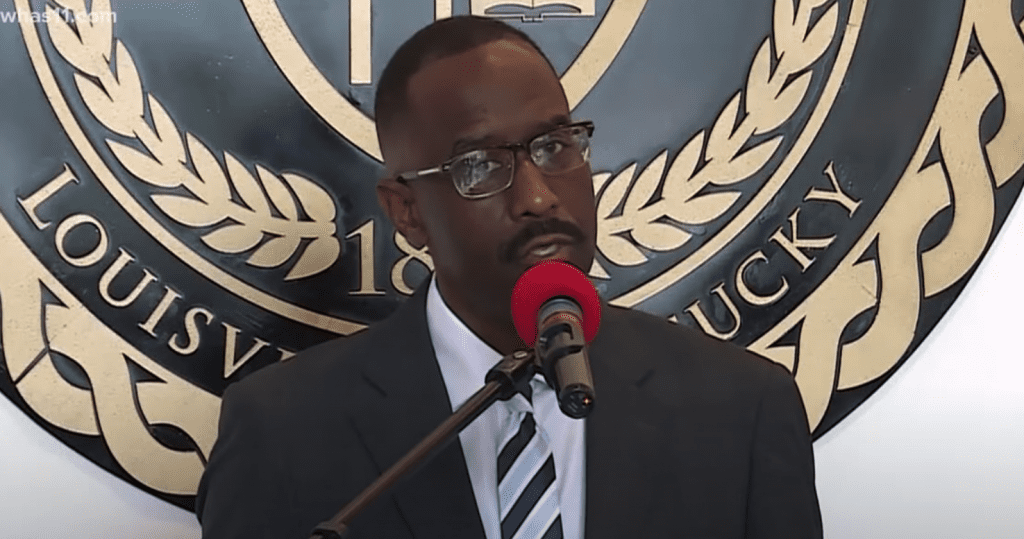

The Rev. Dr. Kevin Cosby is president of Simmons College and pastor of St. Stephen Baptist Church. This op-ed was published in the Louisville Courier-Journal October 3, 2018 and reprinted here with permission.