By Lindsay Bruehl

I haven’t always been this way

I wasn’t born a renegade

I felt alone, still feel afraid

I stumble through it anyway

I wish someone would’ve told me that this life is ours to choose

No one’s handing you the keys or a book with all the rules

The little that I know I’ll tell to you

When they dress you up in lies and you’re left naked with the truth

These words from the singer/songwriter Pink, who wrote the song All I Know So Far to her daughter, mirror a similar moment of nakedness with the truth that Ruth, Naomi and Orpah experienced.

Prior to 2015, I would say that I had a good idea of what the story of Ruth was telling me. I would not say I understood everything. I was drawn to the fact the title of the book is Ruth; so clearly Ruth must be the heroine I am trying to imitate. I never meditated on what that meant exactly, considering what she had to do to survive later in the story. That part did not stand out as clearly to me as her choosing the one true God and not giving up on Naomi.

Orpah, on the other hand, I was taught I should not be like. Her faith was not strong enough to keep going and she returned to her home and to her gods. No, I needed the faith of Ruth so I too could have my name listed in the story of salvation.

I barely even thought about Naomi. I saw her as simply a woman Ruth loved and kept my focus on Ruth. The year 2015 took me to a place spiritually where I could see a much bigger picture. I, too, had a story fail me both personally and in our communal life together in the travesty that is our politics.

My husband and I went with the truth in a situation that was nearly impossible to breathe through and believe we were actually experiencing. Going by way of the truth left us with so much loss that I could not stay in that world anymore. Then when I saw how cruel our politics was becoming with the church remaining silent in a moment that needed a prophetic voice, I lost that community too. This time it was by choice. I felt alone. I did not understand how I was living in a world like this or how to keep moving knowing it was this cruel. My tears flowed freely everywhere I went. I could not stop them, not even when I went to Wal-Mart or work.

We as a family had to make a change to survive. I am now here at Perkins, preaching, because of the changes we made. I am doing something that I was told was closed to me based on my gender. The script I was handed was a bunch of rules, and those rules failed. Patriarchy has never served anyone well; Ruth, Naomi and Orpah were failed by it too. There is no book with all the rules. The story of Ruth is not about the rules of faith.

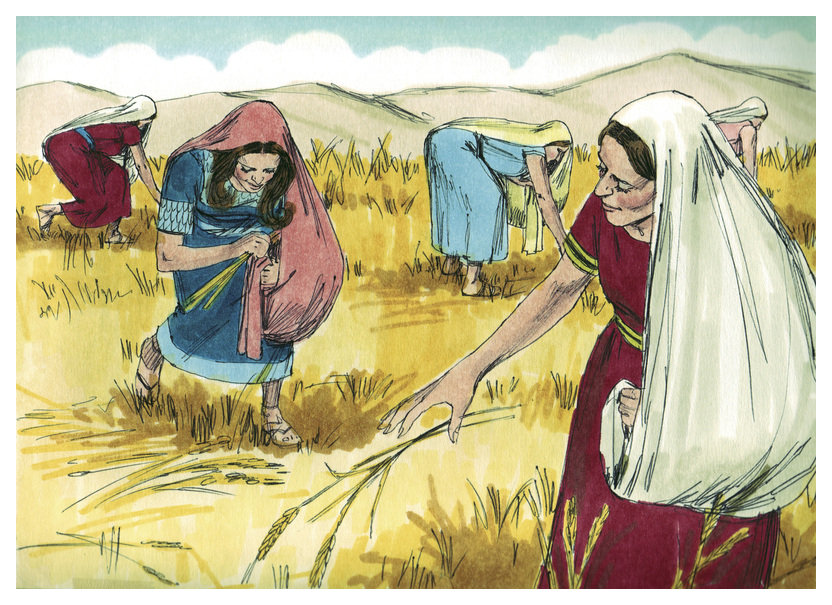

Now when I read this story, I hear the voices of women who were failed by a system. Their feelings are demonstrated in this book—there is weeping and kissing. I can feel their grief and love even now. Feelings are rarely spelled out about in Hebrew scripture. It is an intentional silence that leads us to think for ourselves, contemplating how we feel about the events The fact they are mentioned in this story means they are important to the story. Orpah’s leaving was not presented negatively in this story. It was presented negatively only by the way we read it and teach it to others.

These women are now exposed to poverty and abuse in a way few of us can even fathom. How often do we not see that life does not come with an instruction manual until we are in deep pain and despair—until we are at the end of ourselves and all we are left with is the naked truth. Each of these women were in a place of learning how to make their own decisions and finding who they are in the story—and it was different for each of the women.

Let’s resist pitting these women against each other; instead, let’s see it through the lens of women organizing and choosing to live fully in a world not meant for them to survive on their own. This is a story demonstrating the power of women who organize.

“Return to your mother’s house.” The Hebrew word Bēt ’im·māh occurs only four times in scripture—in Ruth, Genesis 24:8 (Rebekah’s story) and twice in the Song of Songs. Is this a signal of women learning to live creatively in patriarchy—of women organizing? Normally, Naomi would be expected to return to her father’s house. Is Naomi’s wrestling with God’s leading her to find her own voice? Scripture calls her “bitter.” I think she felt deep grief. Grief is the feeling of loss; grief is love.

I remember how my body felt when I felt completely abandoned by God and my community. I asked one of my former pastors why I felt so weird. He told me it was grief. Ruth, Naomi and Orpah each have their individual stories. leading them to their own liberation as they go through their grief. working together. Naomi is learning she has a voice and is worthy as she is. The story her fellow-humans told her was false. God heard her and Israel’s redemption story is continued.

Now let’s look at Ruth and Orpah, starting with the fact that both were Moabites. We have no indication of how Naomi felt about these women whom her sons married. These marriages would have been prohibited by Hebrew law. Moab was thought of as a scandalous place of Lot’s daughters. It’s another example of how diminishing the worth of people often comes out in words that also denigrate women. This is something we do still today. Whatever she felt about these daughters at first, we know she came to love them. She wants them to stay, remarry, find security, and be dealt with kindly as they have dealt kindly with her. There is nothing in the story that says she saw Ruth’s decision as more honorable than Orpah’s. Misinterpreting this story can have disastrous consequences, even as it has in our own American history. I have since learned that Orpah is a central figure to women who are marginalized. I was surprised by what I learned when I took a closer look.

In our American history, this story has been used as justification for the oppression of indigenous women. The stories of both Ruth and Orpah are true and good when we interpret them in ways that liberate. But there is another way to see the story that flips the script on Ruth. Ruth did have faith that helped redeem Israel and Naomi’s story; but it came at a cost to Ruth. Orpah’s story reveals that.

My husband’s grandmother is an indigenous woman who was raised in a boarding school in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma. She is 94-yearsold, and I went to speak with her earlier this month about what had happened and how she was placed in that school. It was an illuminating experience that I will never forget. I had heard bits and pieces of her story but never from her own mouth. My seminary training was vital in knowing what questions to ask and how I needed to respond when I heard parts of her story that were grievous, and when Christianity was used to justify it. I venture to say that no one would be happy to know how our own faith tradition’s theology was used to justify the colonization of a people.

And the misinterpretation of Ruth’s story by Thomas Jefferson, our third president and a founding father, is largely how we got here. This played out in tragic ways that we are still not over. My own husband’s family is affected by it. Dr. Habito told me that Jake’s grandmother, Irene Wapskineh Wheeler, may not be part of my biological family history, but she is my history through marriage. And this healing that is happening is part of my salvation too. Healing is happening in the telling of her story and my receiving it.

In honor of my husband’s family, I looked at this story from an indigenous perspective. That is how I discovered how Thomas Jefferson used Ruth’s story to conquer indigenous women. The Israelites hypersexualized the Moabite women and the early colonist men did this to indigenous women too. Thomas Jefferson used Ruth’s action of uncovering Boaz’s feet as he slept and what happened next as a theology for saying that both Moabite women and American Indian women are agents of “evil and sexual impurity.” He thought indigenous men were weak because of the women, and described their features and mannerisms in detail as to why he thought they were weak.

Instead of viewing Ruth as an example of interethnic bonding and how to survive as a stranger in a land where Israelites were told repeatedly not to harm her, her story was told as her turning her back on Moab and converting to Israel’s God. This is how xenophobia and ethnic cleansing were justified.

But even with the privilege of mixing, American Indians (indigenous peoples) are highly suspicious of that as well. Thomas Jefferson believed there was an irresolvable problem–an “Indian Problem.” He believed the mixing of blood would take the indigenous out of them eventually and the superior blood would spread over the land. Jefferson believed the marriage of Ruth and Boaz was doing the same thing –leading to social absorption. Further, Ruth’s assimilation is complete through Obed’s (Ruth’s baby with Boaz) transfer to Naomi and Boaz. Ruth’s agency in the beginning is diminished in the end and her story is absorbed into the story of Israel, back to the patriarchs after women working together brought about the salvation story for Israel once again. The story of Rahab, Ruth’s mother-in-law, can be told in similar fashion.

This is a hard interpretation of a story that comes at a crucial and important time in Israel’s salvific history. I was recently listening to Rabbi Nancy Kasten, co-founder of the nonprofit Faith Commons, when she said this: “There is no one way to read scripture. The goal we should have is to do no harm. But know when we present a story, that is not the only way the story can be told.”

This is true for the story of Ruth. We can lament the history that has used Ruth’s story to harm our own siblings in our American history. But we can also rejoice that indigenous people can find their story of salvation in scripture too. Through Orpah, their pain and story are known. When we allow the truth in, the naked truth (not the truth as we wish it were), we can find the character of God. We do not serve a God who believes anyone should be assimilated and conquered.

Can the Ruth story be read that way? Sure. But is that the God we know in scripture overall? I rarely say “must” in a sermon, but we must be careful. It is important to meditate on scripture often to know who God is. These sacred words have the power of life and death.

When I talked to Jake’s grandmother, she told me she still believes what she had been taught. She told me that she knows Methodists are a derivative of the Catholic faith. I reminded her that I am Baptist, and she said she knew that Baptists operate differently. She told me she was prevented from co-mingling with people like me growing up. So, in knowing that, we can hear a woman who had been colonized by a faith she still believes in whole-heartedly and who was even taught to not be around people like me. She is now telling her story to a woman like me, a Baptist. This is how women organize. This is how we get to the redeeming/healing work of God.

As I finished writing this sermon, Pink’s words from All I Know So Far came to me again:

So you might give yourself away, yeah

And pay full price for each mistake

But when the candy coating hides the razor blade

You can cut yourself loose and use that rage

I wish someone would’ve told me that this darkness comes and goes

People will pretend but, baby girl, nobody knows

And even I can’t teach you how to fly

But I can show you how to live like your life is on the line

Lindsay Bruehl is a third-year Baptist student at Perkins School of Theology, Dallas, Texas. This sermon was delivered in Chapel on October 28, 2021.