By Patrick Anderson, editor

While traveling in Africa along with a small group of pastors a few years ago, I spent several days at a lodge near the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia, on the edge of what was commonly called Victoria Falls.

The Batonga people have been living in that area for hundreds of years and they, along with other tribes, named the falls Mosi-oa-Tunya, “the smoke that thunders.” When seen from afar, one’s senses are filled with the sight of the smoke-like mist soaring into the sky from the falls. The thunderous sound of the Zambezi River’s massive drop-off, creating the world’s largest sheet of cascading water, is overwhelming. Clearly, the name has been well-known for many centuries. And what an appropriate name it is!

In 1855, a white fellow named David Livingstone trekked through the area and perhaps was the first white person to see the falls. He quickly claimed to have discovered the place, renaming it for an English monarch who had no idea where the falls were or who was living nearby. Certainly, the folks living in the region were unaware of either the claim of “discovery” or the renaming.

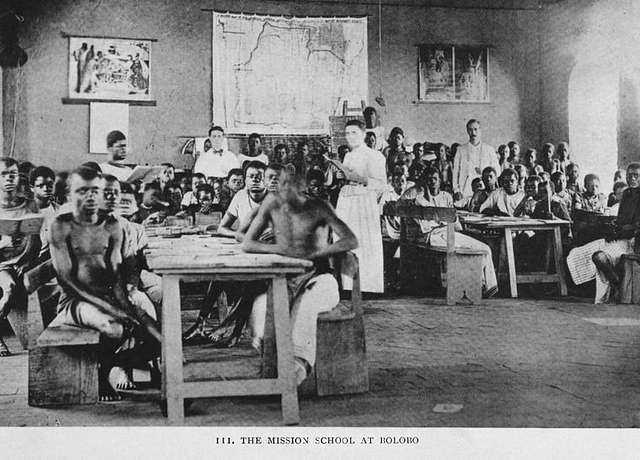

Scottish missionaries were part of a long succession of Christians to enter lands where millions of people, previously unseen by Europeans met them, sometimes innocently with smiling faces and open arms, and sometimes with fear and violence. The newcomers invariably arrived with a sense of their own superiority, claiming the land for themselves, their nations and their God.

The sense of European superiority over Africans was a commonly held mindset, applied not only to Africans, but to indigenous peoples all around the world. The newcomers awed indigenous people with firearms, trinkets, clothing and utensils deemed to be superior.

The arrival of explorers and discoverers to the “New World” during the 15th century and for hundreds of years thereafter dramatically changed the world.[1] The impetus for that was largely driven and justified by church and state-sponsored rationales and doctrines. Lands and people were mastered for the benefit of monarchs and understood to be necessary for the evangelization of heathens. The belief in the superiority of invaders was both explicit and implicit.

Two doctrines birthed in the Christian faith inaugurated and sustained systems of domination and exploitation: the “Doctrine of Discovery” espoused 500 years ago, and its companion “Doctrine of White Superiority.” I contend that those doctrines (let’s call them heresies), formalized a Christian justification for very unchristian behaviors—behaviors which have driven much of the systemic ills of our world today.[2]

The global economy demonstrates the wide disparities between rich “discovering” nations and people and poor “discovered” nations and people. The ascendancy of the belief in “white superiority,” which in recent decades had been considered (primarily by white folks), to be somewhat dormant is alive and well in the 21st century.

The Doctrines of Discovery and Dominion

The Doctrine of Discovery was invoked by the Roman Catholic Church in the 15th century through three papal bulls.[3] The popes justified and enabled European “discovery” of “new lands” and the killing or enslavement of indigenous people, with eradication of cultures, and theft of resources and land from any “non-Christian” inhabitants.

The 15th century doctrine was primarily directed toward the lands we now recognize as the Americas; but the same justifications enabled seizing lands and enslaving people in Africa as long as they were not Christians. Although the doctrine itself was nullified in the 1530s, Spain and Portugal and other European countries had already enthusiastically embarked on an unstoppable worldwide enterprise to seek out lands, find treasure and “Christianize,” enslave, or eradicate inhabitants. Americans will best remember Pope Alexander VI’s Inter caetera (1493) which provided the rationalization for Christopher Columbus’ opening of the New World for colonization.

The 500 years following the establishment of the doctrine and the lingering structural effects of that doctrine are evidenced in economic disparities between descendants of the oppressed and descendants of the oppressors. Westerners are likely to understand those effects most vividly by studying colonization on Africa and Central and South American countries.[4] The undeniable fact is that people who claimed to be committed to Jesus Christ invoked and justified social policies and human behaviors that nurtured a lion’s share of the ethnic, economic, political and legal inequities in the world today.

In the United States of America, the Doctrine of Discovery morphed into the “doctrine of manifest destiny” by which Western monarchies, and then European invaders in the 1600s began the process of claiming land, subjugating or eradicating inhabitants on those lands, building an economy and infrastructure with the unpaid labor of slaves by any means necessary—all with the theological blessings of Christian apologists.

One legal outcome is characterized the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1823 ruling that indigenous people had only rights of “occupancy,” not ownership, over lands on which they had long lived. In the 19th century then, the land was open for the taking, cited in 2005 as “precedent” in a case in upstate New York involving the Oneida Indian Nation.

In Africa, the invasion of lands rich with natural resources and human capital of European powers led to brutal conquest and dominion. In South Africa as early as 1652 and for more than 300 years thereafter, we can see first the enslavement of Africans and their shipment as cargo out of the continent, then the exploitation of African labor in the plantations and mines, followed by a mad scramble by seven European countries (Belgium, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal) to partition and exploit the continent for profit for the benefit of Europe which they understood to be their rightful privilege. The callous mapping and partitioning of the continent were conducted without regard for geography, ethnic populations, traditional cultural values or tribal relations. Much of Africa continues to be characterized by corruption, tribal genocide and extreme destitution. The continued impoverishment and plunder can be recognized through a form of “debt slavery” whereby the continent, impoverished by this sordid history, is now financed by developed countries through the World Bank, with its riches in competition by more recent world powers like China and Russia.

Christian denominations in the West are consoled by the fact that, despite all of the demonstrable ills laid at the Church’s doorstep, the result of missionary fervor and courage in the 19th and 20th centuries resulted in today’s large percentage of Africans who describe themselves as Christian. Indeed, many African Christians have set a very high bar for following Jesus, Christian scholarship, devotion to alleviating human suffering and prophetic faith.

The Doctrine of White Superiority and a Biblical Justification for Chattel Slavery

In the 1840s, major Christian Protestant denominations in America split along North and South lines over theological arguments regarding justification for and opposition to slavery. In earlier years Baptists and Methodists generally opposed slavery, but as churches were planted throughout the South, slaveholding churches and church leaders gained greater theological and financial influence. Leading up to and during the Civil War and in the immediate aftermath of that war, the differences between North and South were heightened.[5] Southern ministers wrote extensively in defense of slavery and in favor of the subjugation of women, using the same or similar biblical texts.

The mindset promoted the idea that a father/master was supposed to be a benevolent and paternalistic overseer of all family (and property) members. After all, the New Testament’s injunctions “for slaves to obey their masters” appeared alongside instructions for wives to “obey their husbands.” White men were placed at the top of the social hierarchy, white women and children next, and slaves at the bottom.[6] This was said to be God’s will.

Historian Bill J. Leonard[7] writes that Richard Furman’s 1822 “biblical defense” of slavery became an important guide for Baptist responses to abolitionism. Furman, pastor of First Baptist Church, Charleston, South Carolina, and namesake of Furman University (my alma mater), declared:

Had the holding of slaves been a moral evil, it cannot be supposed, that the inspired Apostles, who feared not the faces of men, and were ready to lay down their lives in the cause of their God, would have tolerated it, for a moment, in the Christian Church… In proving this subject justifiable by Scriptural authority, its morality is also proved; for the Divine Law never sanctions immoral actions.

Leonard writes:

Furman and other pro-slavery Baptists made support for slavery essential to biblical orthodoxy, implying that if the Bible was wrong in sanctioning slavery, it might be untrustworthy on the nature of salvation itself. Their literal method of interpreting the Bible aided Baptists in claiming biblical authority to support the institution of chattel slavery.

In support of Furman’s thought, South Carolina pastor Richard Fuller wrote of slavery:

…both testaments constitute one entire canon, and that they furnish a complete rule of faith and practice.” He concluded: WHAT GOD SANCTIONED IN THE OLD TESTAMENT, AND PERMITTED IN THE NEW, CANNOT BE A SIN.

National politics in America have been embroiled in theological disputes about slavery throughout much of the 18th and 19th centuries. In October of 1858 during the height of the Lincoln and Douglas debates, Abraham Lincoln wrote a scathing indictment of those who claimed that since slavery was present in the Bible, it must have met with God’s approval.[8] Lincoln began by observing that if Blacks were truly inferior to whites, then as good Christians, should not whites provide more to those in need instead of taking what little they had? He summed this idea up by writing:

‘Give to him that is needy’ is the Christian rule of charity; but ‘Take from him that is needy’ is the rule of slavery.

As a good thing, slavery is strikingly peculiar, in this, that it is the only good thing which no man ever seeks the good of, for himself.

Lincoln focused his attention on those who claimed that it was the will of God that African Americans were enslaved. He noted that it was up to man, more specifically the slave owner, to determine what precisely was the “will of God” regarding the plight of the slave. Mentioning specifically Reverend Frederick Ross who the previous year had published a book entitled Slavery Ordained of God, Lincoln poses a simple question. If the slave owner is the one interpreting “God’s will,” would Reverend Ross voluntarily choose to surrender his slave and thereby be forced to work for his own bread, or retain his slave and continue to enjoy the benefits that slave provided?”

Theological justification from their ministers allowed Southerners to believe that “not only did God sanction slavery, but slavery’s supporters were better Christians and more faithful interpreters of Biblical text than were their opponents.” The slave-owning class was small, but it was supported by the overwhelming majority of churches and ministers in the South.

Considering that they saw themselves as doing God’s work, white Southerners were shocked by the military defeat of the Confederacy. But they refused to see this defeat as a divine judgment on their beliefs and actions. Instead, they transformed the defeat into a belief that it was “the action of a mysterious, yet all-wise Providence and an opportunity to correct failings in personal piety.”

Proslavery theology persisted because “religious arguments had situated slavery amidst other forms of household order and had relied upon widely accepted views of women’s subordination as a corollary to slaves’ deprivation of rights.” Southern Christians defeated Reconstruction and kept their “antebellum worldview,” reaffirming it as they helped rebuild the legal and social structures of white supremacy through terrorism and with Northern indifference.

Although one is hard pressed to identify prominent Southern Christians who publicly opposed slavery, the literature of Christians devoted to emancipation, equal rights, justice and reparations for freed slaves is impressive. The passage of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, designed to fully incorporate former slaves into the fabric of American democratic life, is due in large measure to those voices. But in a very short time after the end of the War Between the States and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, terrible widespread violence by white mobs against Black citizens, often while wielding Christian symbols, engendered many decades of continued disenfranchisement, injustice, economic and social inequities throughout America.

Conclusion

Recently, Pope Francis publicly repudiated the “Doctrine of Discovery.” The medieval popes justified, enabled and profited from eradication of cultures and theft of resources and land. The Roman Catholic Church was enriched by proceeds from the stolen precious metals and vast treasures. Pope Francis, as the proper descendant and ecclesiastical heir of the earlier popes, wrestles with how repudiation of a heresy compensates for the heresy.

Twenty-first century Christians in America face the same questions regarding slavery and the long system of inequality engendered. Earlier this summer, the General Council of the Baptist World Alliance (BWA) meeting in Stavanger, Norway, representing more than 40 nations, passed a resolution unanimously repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery. However, few white American Christians, while benefiting from the advantages enjoyed by all white descendants of centuries of the enterprise of American slavery, are seriously engaged with the on-going challenges of needs for reparations and justice for descendants of American slavery.

We also face political conflicts over how we should reckon with our nation’s fractious history. Many states continue to struggle with debates about Confederate statues in public places. We have been put to the test by angry reactions to The New York Times’ series on the 1619 Project and are reeling from Florida’s recent policies of rewriting or eliminating school history curricula. Ironically, the Critical Race Theory social science scholars will ultimately be vindicated in much the same way Galileo was vindicated for stating the obvious before irrational critics.

Christians have an obligation to contend with effects of the white world’s misinterpretation and misuse of the teachings of Jesus Christ and our complicity in the exercise of the doctrines of dominion and white supremacy. Perhaps by doing so we will comprehend and remedy the structures and conditions that have resulted from those doctrines.

[1] Many sources chronicle the horrors of colonialism. Perhaps a leading example is Joseph Conrad’s novel, The Heart of Darkness (1899), which describes King Leopold’s hellish role in Congo, using Presbyterian missionaries’ journals and other contemporaneous sources for factual accuracy.

[2] I do not claim to have credentials of a scholarly theologian, but as a social scientist I am informed about social policy, religious influence, and cause and effect relationships in the mindset and worldview of influential advocates for theological viewpoints that have justified untold violence against the teachings and life of Jesus.

[3] Pope Nicholas V’s Dum diversas (1452) and Romanus Pontifex (1455); and Pope Alexander VI’s Inter caetera (1493).

[4] Among many sources to inform our understanding of this fact are found in:

[5] Elizabeth L. Jemison writes in her exploration of proslavery Christianity after Emancipation.

[6] See “Proslavery Christianity After the Emancipation” By: Elizabeth L. Jemison, Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 72, No. 4 (WINTER 2013), pp. 255-268.

[7] Bill J. Leonard, Ministry Matters, “Slavery and Denominational Schism”, August 18, 2011.

[8] Lincoln’s handwritten notes from that time can be seen at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Washington, D.C.