By Tony Campolo

Words, say experts on language, gain their meaning by how they are used within the social context that employs them. As a case in point, many theologically orthodox Christians during the first half of the 20th century had no problem using the label “fundamentalist” to define themselves. That label, however, gradually became associated with connotations which many found undesirable.

Following the famous 1925 Scopes trial in Tennessee, which made rejecting Darwin’s theory of evolution a defining commitment in most fundamentalist circles, those who had used the label, were viewed as anti-scientific, and even anti-intellectual.

As time went on, fundamentalists increasingly came to be viewed as Christians who embraced a pietistic lifestyle marked by strong opposition to using any kind of alcoholic beverage, dancing and, in extreme cases, going to the movies, and even the use of “make-up” by women.

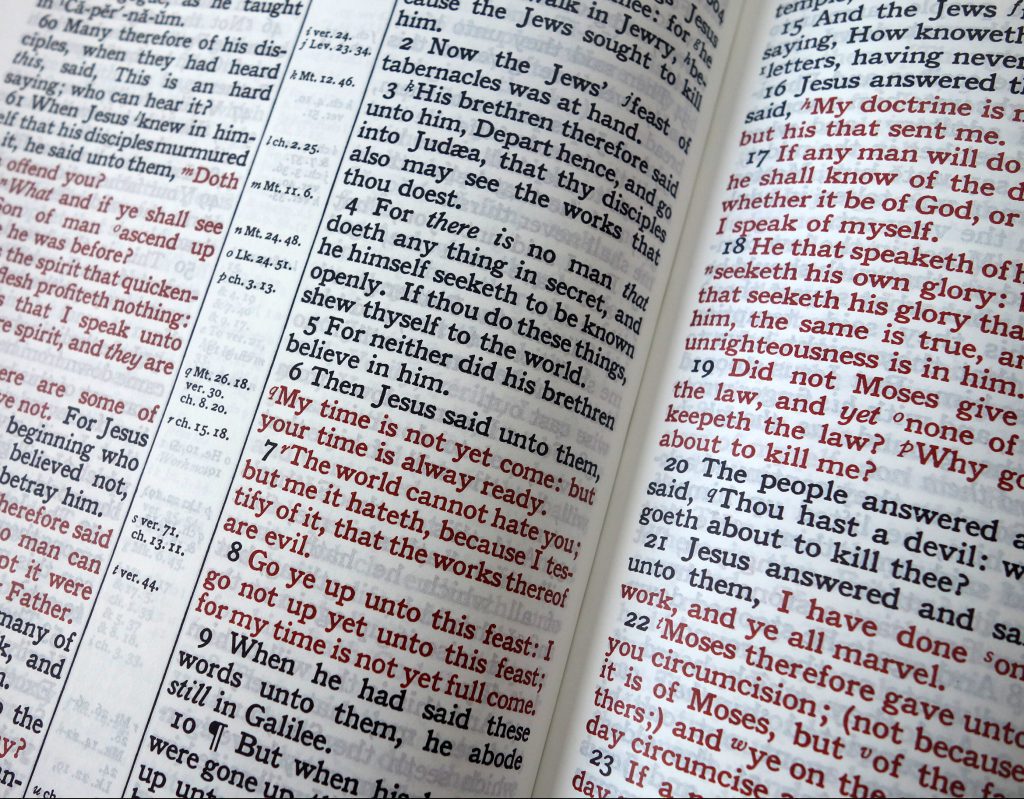

More important, among fundamentalists, there was widespread affirmation of the theology of John Nelson Darby, commonly referred to as dispensationalism. This theology was popularized via the Scofield Reference Bible, which had footnotes that explained Bible verses in accord with Darby’s beliefs, and became a standard text for fundamentalists. Growing up, I remember singing, along with my fundamentalist teenage friends:

My hope is built on nothing less

than Scofield notes and

Scripture Press.

The impact of the Scofield Reference Bible in molding the fundamentalist mindset cannot be underestimated. It is a theology that has diminished the importance of social justice activism among church people.

Finally, it must be noted that fundamentalists somewhat have gained the reputation in the opinion of many as being judgmental and, in some cases harshly so, of anyone who differed with either their prescribed theology or designated lifestyle.

Given these realities, it is not surprising that many Christians no longer wanted to assume the label “fundamentalist” for themselves. Instead, many prominent Christian leaders, such as Billy Graham and Carl Henry (the editor of Christianity Today magazine) increasingly identified themselves as “evangelicals.”

Sadly, as of late, this new title gradually has taken on negative connotations in the secular media. As evangelicals increasingly came to be identified on television and in newspapers as being Christians who are against gays and lesbians, questioning much about the movement for women’s rights, against non-Anglo immigrants and being anti-Muslim, the label “evangelical” became increasingly problematic for many Christians. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the rhetoric during the political campaigns of 2016.

A few years ago, Jim Wallis of Sojourners magazine called together a group of mostly young Christian leaders who faced the question as to whether the name “evangelical” had lost its meaning for us. We were still Christians who believed in the doctrines of the Apostle’s Creed, declared that salvation comes via surrendering to the spiritual presence of the resurrected Christ, and held a belief that scripture was written by persons who were inspired and directed by the Holy Spirit.

As we pondered together what to call ourselves, we came up with the name “Red Letter Christians.” It was our belief that the name was relevant for our times, primarily because the red letters of the Bible, which emphasize the words spoken by Jesus, spell out a radical counter-cultural lifestyle which orthodox believers are often prone to ignore. For instance, many of us believe that when Jesus said “blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy,” that precluded the practice of capital punishment and, when Jesus taught us in those red letters to love our enemies, He probably meant we shouldn’t kill them. And when He called for radical sacrificial giving to the poor, as He did in Mark 10, we believe that Jesus was serious.

We think that what Jesus spelled out in the Sermon on the Mount is superior to any ethic we find in the Old Testament. We say this because Jesus declares it to be so, especially in Matthew 5. What he has to say in that chapter about such things as divorce, retaliation toward those who have hurt us, and anger, proves to be a higher standard for us to live by than even what the Hebrew prophets had to say.

There are those who try to discredit our movement by suggesting that we negate those other parts of the Bible apart from the red letters. Nothing could be further from the truth. We believe that the rest of the Bible points to Jesus and, like the early church, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, we find the nature and mission of Jesus spelled out throughout the entire Hebrew Bible. Beyond that, we believe that the rest of the Bible can be understood only insofar as it is read through the eyes of the Jesus revealed in the red letters.

Red Letter Christians have very few problems with the theology of evangelicals. Our problems are with the identity they have established and the politics they have embraced and, in some cases, even sanctified. We argue that Jesus is neither a Republican nor a Democrat and to cast Him as the legitimator of any political ideology is idolatry.

Given the existential situation that we face here in America, we believe that the label “Red Letter Christians” (www.redletterchristians.org) is a label whose time has come.

—Tony Campolo is an American Baptist, sociologist, pastor, author, public speaker and former spiritual advisor to U.S. President Bill Clinton. Known primarily for his work with Red Letter Christians, and the Campolo Centre as well as authoring over 40 books including, Red Letter Revolution: What If Jesus Really Meant What He Said? and Following Jesus Without Embarrassing God. He is an emeritus member of the Board of Christian Ethics Today.