By Raphael Warnock

Mr. President, before I begin my formal remarks, I want to pause to condemn the hatred and violence that took eight precious lives last night in metropolitan Atlanta. I grieve with Georgians, with Americans, with people of love all across the world. This unspeakable violence, visited largely upon the Asian community, is one that causes all of us to recommit ourselves to the way of peace, an active peace that prevents these kinds of tragedies from happening in the first place. We pray for these families.

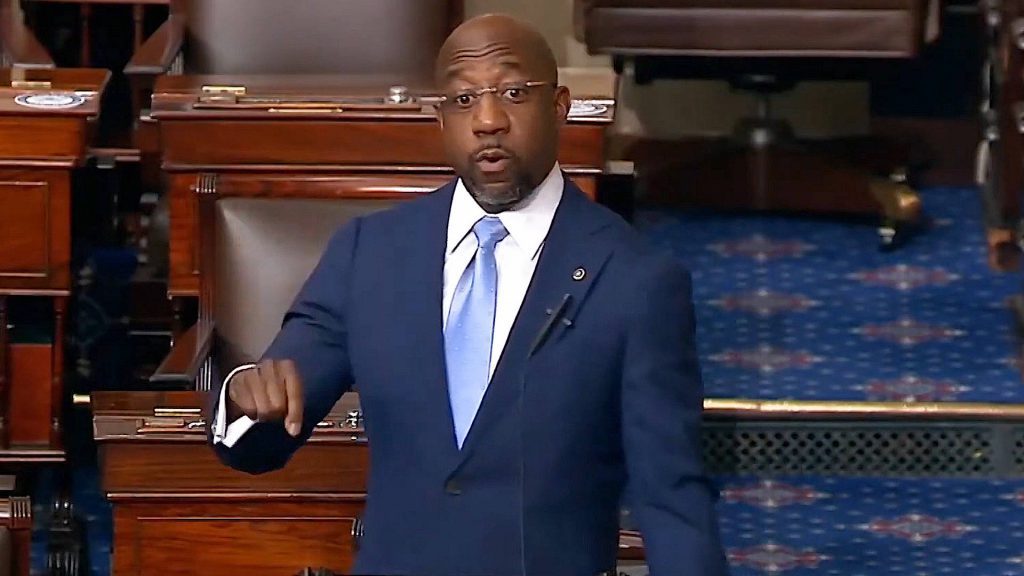

Mr. President, I rise here today as a proud American and as one of the newest members of the Senate, in awe of the journey that has brought me to these hallowed halls, and with an abiding sense of reverence and gratitude for the faith and sacrifices of ancestors who paved the way.

I am a proud son of the great state of Georgia, born and raised in Savannah, a coastal city known for its cobblestone streets and verdant town squares. Towering oak trees, centuries old and covered in gray Spanish moss, stretched from one side of the street to the other, bend and beckon the lover of history and horticulture to this city by the sea. I was educated at Morehouse College, and I still serve in the pulpit of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, both in Atlanta, the cradle of the civil rights movement. And so, like those oak trees in Savannah, my roots go down deep, and they stretch wide, in the soil of Waycross, Georgia, and Burke County and Screven County. In a word, I am Georgia, a living example and embodiment of its history and its hope, of its pain and promise, the brutality and possibility.

Mr. President, at the time of my birth, Georgia’s two senators were Richard B. Russell and Herman E. Talmadge, both arch-segregationists and unabashed adversaries of the civil rights movement. After the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board ruling outlawing school segregation, Talmadge warned that blood will run in the streets of Atlanta. Senator Talmadge’s father, Eugene Talmadge, former governor of our state, had famously declared, “The South loves the Negro in his place, but his place is at the back door.” When once asked how he and his supporters might keep Black people away from the polls, he picked up a scrap of paper and wrote a single word on it: “pistols.”

Yet, there is something in the American covenant — in its charter documents and its Jeffersonian ideals — that bends toward freedom. And led by a preacher and a patriot named King, Americans of all races stood up. History vindicated the movement that sought to bring us closer to our ideals, to lengthen and strengthen the cords of our democracy. And I now hold the seat, the Senate seat, where Herman E. Talmadge sat.

And that’s why I love America. I love America because we always have a path to make it better, to build a more perfect union. It is a place where a kid like me who grew up in public housing, the first college graduate in my family, can now stand as a United States senator. I had an older father. He was born in 1917. Serving in the Army during World War II, he was once asked to give up his seat to a young teenager while wearing his soldier’s uniform, they said, “making the world safe for democracy.” But he was never bitter. And by the time I came along, he had already seen the arc of change in our country. And he maintained his faith in God and in his family and in the American promise, and he passed that faith on to his children.

My mother grew up in Waycross, Georgia. You know where that is? It’s “way ‘cross” Georgia. And like a lot of Black teenagers in the 1950s, she spent her summers picking somebody else’s tobacco and somebody else’s cotton. But because this is America, the 82-year-old hands that used to pick somebody else’s cotton went to the polls in January and picked her youngest son to be a United States senator.

Ours is a land where possibility is born of democracy — a vote, a voice, a chance to help determine the direction of the country and one’s own destiny within it, possibility born of democracy. That’s why this past November and January, my mom and other citizens of Georgia grabbed hold of that possibility and turned out in record numbers: 5 million in November, 4.4 million in January — far more than ever in our state’s history. Turnout for a typical runoff doubled. And the people of Georgia sent their first African American senator and first Jewish senator, my brother Jon Ossoff, to these hallowed halls.

But then, what happened? Some politicians did not approve of the choice made by the majority of voters in a hard-fought election in which each side got the chance to make its case to the voters. And rather than adjusting their agenda, rather than changing their message, they are busy trying to change the rules. We are witnessing right now a massive and unabashed assault on voting rights unlike anything we’ve ever seen since the Jim Crow era. This is Jim Crow in new clothes.

Since the January election, some 250 voter suppression bills have been introduced by state legislatures all across the country, from Georgia to Arizona, from New Hampshire to Florida, using the big lie of voter fraud as a pretext for voter suppression, the same big lie that led to a violent insurrection on this very Capitol — the day after my election. Within 24 hours, we elected Georgia’s first African American and Jewish senator and, hours later, the Capitol was assaulted. We see in just a few precious hours the tension very much alive in the soul of America. And the question before all of us at every moment is: What will we do to push us in the right direction?

And so, politicians, driven by that big lie, aimed to severely limit — and, in some cases, eliminate — automatic and same-day voter registration, mail-in and absentee voting, and early voting and weekend voting. They want to make it easier to purge voters from the voting roll altogether. And as a voting rights activist, I have seen up close just how draconian these measures can be. I hail from a state that purged 200,000 voters from the roll one Saturday night, in the middle of the night. We know what’s happening here: Some people don’t want some other people to vote.

I was honored on a few occasions to stand with our hero and my parishioner, John Lewis. I was his pastor, but I’m clear he was my mentor. On more than one occasion, we boarded buses together after Sunday church services as part of our Souls to the Polls program, encouraging the Ebenezer church family and communities of faith to participate in the democratic process. Now, just a few months after Congressman Lewis’ death, there are those in the Georgia Legislature, some who even dare to praise his name, that are now trying to get rid of Sunday Souls to the Polls, making it a crime for people who pray together to get on a bus together in order to vote together. I think that’s wrong. Matter of fact, I think that a vote is a kind of prayer for the kind of world we desire for ourselves and for our children. And our prayers are stronger when we pray together.

To be sure, we have seen these kinds of voter suppression tactics before. They are a part of a long and shameful history in Georgia and throughout our nation. But, refusing to be denied, Georgia citizens and citizens across our country braved the heat and the cold and the rain, some standing in line for five hours, six hours, 10 hours, just to exercise their constitutional right to vote — young people, old people, sick people, working people, already underpaid, forced to lose wages, to pay a kind of poll tax while standing in line to vote.

And how did some politicians respond? Well, they are trying to make it a crime to give people water and a snack as they wait in lines that are obviously being made longer by their draconian actions. Think about that. Think about that. They are the ones making the lines longer, through these draconian actions. And then they want to make it a crime to bring grandma some water while she’s waiting in a line that they’re making longer. Make no mistake: This is democracy in reverse. Rather than voters being able to pick the politicians, the politicians are trying to cherry-pick their voters. I say this cannot stand.

And so, I rise, Mr President, because that sacred and noble idea — one person, one vote — is being threatened right now. Politicians in my home state and all across America, in their craven lust for power, have launched a full-fledged assault on voting rights. They are focused on winning at any cost, even the cost of the democracy itself. And I submit that it is the job of each citizen to stand up for the voting rights of every citizen. And it is the job of this body to do all that it can to defend the viability of our democracy.

That’s why I am a proud co-sponsor of the For the People Act, which we introduced today. The For the People Act is a major step in the march toward our democratic ideals, making it easier, not harder, for eligible Americans to vote by instituting commonsense, pro-democracy reforms, like establishing national automatic voter registration for every eligible citizen and allowing all Americans to register to vote online and, on Election Day; requiring states to offer at least two weeks of early voting, including weekends, in federal elections, keeping Souls to the Polls programs alive; prohibiting states from restricting a person’s ability to vote absentee or by mail; and preventing states from purging the voter rolls based solely on unreliable evidence, like someone’s voting history — something we’ve seen in Georgia and other states in recent years. And it would end the dominance of big money in our politics and ensure our public servants are there serving the public.

Amidst these voter suppression laws and tactics, including partisan and racial gerrymandering, and in a system awash in dark money and the dominance of corporatist interests and politicians who do their bidding, the voices of the American people have been increasingly drowned out and crowded out and squeezed out of their own democracy. We must pass For the People so that people might have a voice. Your vote is your voice, and your voice is your human dignity.

But not only that, we must pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. You know, voting rights used to be a bipartisan issue. The last time the voting rights bill was reauthorized was 2006. George W. Bush was president, and it passed this chamber 98 to 0. But then, in 2013, the Supreme Court rejected the successful formula for supervision and preclearance contained in the 1965 Voting Rights Act. They asked Congress to fix it. That was nearly eight years ago, and the American people are still waiting. Stripped of protections, voters in states with a long history of voter discrimination and voters in many other states have been thrown to the winds.

We Americans have noisy and spirited debates about many things — and we should. That’s what it means to live in a free country. But access to the ballot ought to be nonpartisan. I submit that there should be 100 votes in this chamber for policies that will make it easier for Americans to make their voices heard in our democracy. Surely, there ought to be at least 60 in this chamber who believe, as I do, that the four most powerful words uttered in a democracy are “the people have spoken,” therefore we must ensure that all of the people can speak.

But if not, we must still pass voting rights. The right to vote is preservative of all other rights. It is not just another issue alongside other issues. It is foundational. It is the reason why any of us has the privilege of standing here in the first place. It is about the covenant we have with one another as an American people: E pluribus unum, “Out of many, one.” It, above all else, must be protected.

And so, let’s be clear. I’m not here today to spiral into the procedural argument regarding whether the filibuster, in general, has merits or has outlived its usefulness. I’m here to say that this issue is bigger than the filibuster. I stand before you saying that this issue — access to voting and preempting politicians’ efforts to restrict voting — is so fundamental to our democracy that it is too important to be held hostage by a Senate rule, especially one historically used to restrict the expansion of voting rights. It is a contradiction to say we must protect minority rights in the Senate while refusing to protect minority rights in the society. Colleagues, no Senate rule should overrule the integrity of our democracy, and we must find a way to pass voting rights, whether we get rid of the filibuster or not.

And so, as I close — and nobody believes a preacher when he says, “As I close” — let me say that I — as a man of faith, I believe that democracy is the political enactment of a spiritual idea: the sacred worth of all human beings, the notion that we all have within us a spark of the divine and a right to participate in the shaping of our destiny. Reinhold Niebuhr was right:

“[Humanity’s] capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but [humanity’s] inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.”

John Lewis understood that and was beaten on a bridge defending it. Amelia Boynton, like so many women not mentioned nearly enough, was gassed on that same bridge. A white woman named Viola Liuzzo was killed. Medgar Evers was murdered in his own driveway. Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman, two Jews and an African American standing up for that sacred idea of democracy, also paid the ultimate price. And we, in this body, would be stopped and stymied by partisan politics, short-term political gain, Senate procedure?

I say let’s get this done no matter what. I urge my colleagues to pass these two bills, strengthen and lengthen the cords of our democracy, secure our credibility as the premier voice for freedom-loving people and democratic movements all over the world, and win the future for all of our children. Mr. President, I yield the floor.

— This address, Senator Raphael Warnock’s first on the US Senate floor, was delivered on March 17, 2021. The speech can be seen in its entirety at: https://www.c-span.org/video/?c4952332/senator-raphael-warnock-maiden-floor-speech