Reviewed by Peter Rhea Jones

The subtitle of this book is a great place to begin: “Memoir of a Survivor of the SBC Unholy War.” Rightly dubbed as memoir, this book is a model of exceptional quality of that genre.

This recent publication about the Southern Baptist controversies of the 1980s with a focus on the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary is worth a careful reading..

Many are familiar with previous accounts of these controversies. One was by a seasoned Southern Baptist denominational leader (Grady Cothen), another consisted of an elaborate series of chapters on aspects and organizations edited by a professional church historian and Baptist specialist (Walter Shurden), and yet another was a defense of the Takeover by one of its two principal leaders whose political expertise aided the effort (Paul Pressler), especially in getting out the vote by busing in voters! During this time, many pastors, untrained in theology but who in Baptist polity had every right to vote in the SBC, weighed in on theological education. Moreover, the author of a recent history of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, whose author claims to have touched a million pieces of data, was not even present at the seminary during the maelstrom.

Dr. Larry McSwain, a “moderate” insider, served on the faculty of Southern Seminary in the 70s and 80s. Thus, we have in this memoir a view from within. He describes for the reader what it was like to be in a seminary under assault, depicting that which was decried when it should have been applauded. Leaving no doubt where he stood (and stands) as a moderate in the controversy, McSwain makes a concerted effort at fairness. Helpfully, he shares interviews from some students about how they felt being in a school under assault.

Roy H. Honeycutt served as president of Southern Seminary during several of the years of the controversy. McSwain makes no attempt to hide his admiration and fondness for Honeycutt. He knew Honeycutt’s heart, his love for the seminary, his integrity, and his efforts both to protect faculty and to deal genuinely with an increasingly hostile fundamentalist board.

Some of us have long known that McSwain himself was an effective and pivotal player during the decade-long struggle. Serving in the roles of dean of the school of theology and provost of the entire seminary placed McSwain in the eye of the storm. His latest book details events yet unpresented, including his efforts at defending the school during these turbulent years.

President Honeycutt and McSwain worked diligently to keep Southern Seminary a healthy seminary as long as possible. They were sensitive to and advocated for a besieged faculty enduring relentless criticism and false accusation. While the teaching there was unapologetically progressive and informed by international theology, it was in turn a privilege for most students. The faculty there was not liberal in the sense of getting their jollies repudiating central theological beliefs. Sophomoric attitudes scornful of the work of local churches were not present at the seminary. However, making the Bible and theology relevant to the real world was a priority. A highly informed faculty that had produced substantial numbers of publications conducted themselves responsibly, and were devoted to students and to the Southern Baptist Convention. That faculty understood the SBC. The academic freedom that prevailed at the seminary then may now be in absentia.

Some fundamentalist-conservatives excuse themselves from their avoidance of the intense struggle for Black rights in the 60s and 70s, saying they just missed it. On the other hand, professors from Southern early on, including McSwain, not only did not miss it, but had to deal with the slings and arrows that accompanied valiant efforts to “speak Christian” into a tense time.

In the judgment of many, Southern Seminary and others of the SBC seminaries belonged to a charmed circle of a short list of the finest seminaries in the entire world, both for quality of academics and preparation for ministry. Southern Seminary since Honeycutt and McSwain has returned to the Calvinism of the first president of the 19th century. However, biblical inerrancy, and not Calvinism constituted the primary issue of the controversy during the 80s. It remains to be seen whether the full-blown Calvinism, represented at Southern today, will benefit Southern Baptists. Undoubtedly, while some good happens at Southern today, much has been lost, especially the progressive influence that could be relevant in such a reactionary time as ours.

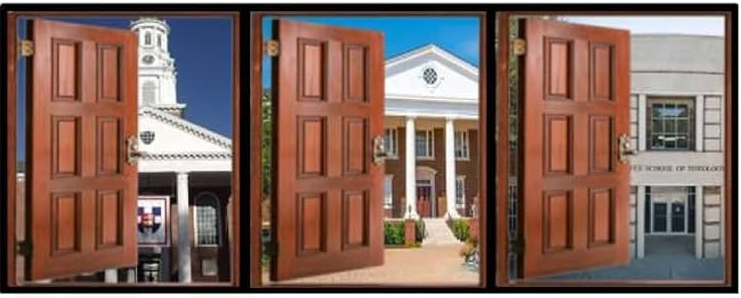

McSwain, his influence far from being cancelled by his painful tour of duty in his high administrative offices, continued to function impressively as a Baptist educator. He served seven eventful years as president of a Baptist college in Rome, Georgia. (Friends of Shorter College and those interested in administration policy in general will be fascinated by his account.) While he admits that raising money was not his greatest gift, he found ways to move the college forward. After his presidential stint at Shorter, McSwain returned to his first love: the classroom. He joined the faculty at McAfee School of Theology in Atlanta, serving for nine good years in both the classroom and administrative roles.

Reliable new information about the controversy can be found in this book. Also, McSwain provides particularly wise advice at the end of his book. Well-written, it is intrinsically interesting. The older reader will be reminded but also informed by the inside story of the unholy war among Baptists in 1980s. The younger reader will be informed about not only what happened but why, meeting the personalities and players and the dynamics that characterized the conflict.

This then is a must-read for many. Those who think they know about the Baptist battle will find out they don’t. At least this was the case for me. Even those who supported the Takeover will benefit from seeing the anguish caused within Southern Seminary. Fundamentalist-conservatives claimed that harm was inflicted on conservative students by critical methodology at Southern. One will find in this book the harm done to good people highly dedicated to theological education, not the least of whom were Honeycutt and McSwain.

Some consolation for moderates has been the creation of several new theological seminaries that permit the continuation of the “Southern Tradition.” McSwain served in one of them

Thank you, Dr. McSwain. Later historians will consult this book because of its historical value and particular nature. Give it a read.

— Peter Rhea Jones, formerly a professor at Southern Seminary 1968-1979, McAfee School of Theology at Mercer University 2000-2016, and pastor of First Baptist Church of Decatur, Georgia 1979-2000.