By Mark Lambert

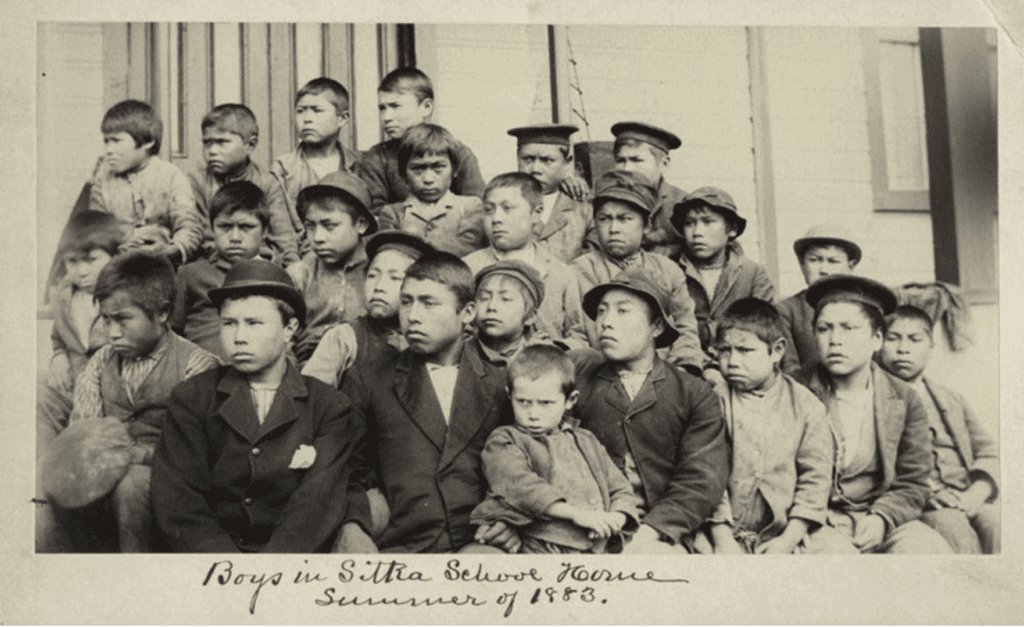

Last month the United States Department of the Interior published the first volume of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. The report confirms, in shocking detail, the US Government’s deployment of boarding schools as a tool to culturally assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children and to facilitate Indian territorial dispossession. More than four hundred of these institutions are documented, in operation between 1819 and 1969.

Perhaps most disturbingly, the report also identifies 53 burial sites for children across the Federal Indian boarding school system—with more expected to be discovered.

The Initiative, pushed by Secretary Deb Haaland, was prompted by the mass discovery of unmarked graves by Canada’s Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc First Nation at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The report contains the first official list of US Federal Indian boarding schools, accompanied by detailed summaries of each school. According to the report, these boarding schools:

“…deployed systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies to attempt to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children through education, including but not limited to the following: (1) renaming Indian children from Indian to English names; (2) cutting hair of Indian children; (3) discouraging or preventing the use of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian languages, religions, and cultural practices; and (4) organizing Indian and Native Hawaiian children into units to perform military drills.”

The report also identifies the frequent use of manual labor and corporal punishment, including flogging, withholding food, and solitary confinement. The Initiative intends to address the intergenerational trauma caused by these institutions. As Secretary Haaland notes,

“We continue to see the evidence of this attempt to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people in the disparities that communities face. It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.”

Regarding the American colonizer’s approach to Indigenous people, cultural assimilation and conversion to Christianity were effectively synonymous concepts—the point was the erasure of Indigenous culture and with it, any resistance to territorial dispossession. I find it striking that this report, produced by a federal agency, attempts to critically—albeit carefully—unravel the role of religion in this chapter of American history.

The 1908 Supreme Court case Quick Bear v. Leupp is singled out, which effectively ruled that the Federal government could freely use funds from Tribal treaty or trust fund accounts to compel children to attend boarding schools operated by religious organizations. In other words, “the Court held that the prohibition on the Federal Government to spend funds on religious schools did not apply to Indian treaty funds… and to forbid such expenditures would violate the free exercise clause of the First Amendment.” Religious institutions are omnipresent actors throughout the report, specifically Christian organizations, and denominations.

The historical role of Christianity in Federal Indian boarding schools is thus one in which the “separation of church and state” simply didn’t apply. To their credit, the investigators do not shy away from this fact, noting, “the United States at times paid religious institutions and organizations on a per capita basis for Indian children to enter Federal Indian boarding schools operated by religious institutions or organizations.” The US Government provided many of these religious groups with tracts of Indian reservation lands and accepted the recommendations of these religious bodies for presidential appointed government posts—all in what the Department deemed “an unprecedented delegation of power by the Federal Government to church bodies.” Notably, this delegation of power was undertaken without any centralized, interdenominational oversight of these religious organizations.

As one example of this close relationship, the Department of the Interior points to the Hilo Boarding School for Native Hawaiian male children, which was founded in 1836 by Calvinist missionaries, received federal funding, and operated as a feeder school for Lahainaluna Seminary. This Seminary then trained Native Hawaiians to convert other Native Hawaiians to Christianity and suppress the Native Hawaiian language (‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i).

My initial interest in the report was pertaining to connections with the history of leprosy in Hawaii, which disproportionately affected the Native Hawaiian population. In cases of suspected leprosy, the 1865 Act of Isolation allowed for the separation of children (including infants) from parents and the relationship between this act and the boarding school system remains a pressing question. The Department does acknowledge the rampant spread of disease throughout Federal Indian boarding schools coupled with the appalling lack of health care. This lack of health care was compounded by the 1883 Religious Crimes Code which explicitly banned the practice of Indigenous ceremonies, including traditional healing methodologies. Curiously, the report does not note this connection or the long-reaching consequences of the 1883 Code, even though Rule Six of that Code warns:

The influence or practice of a so-called “medicine-man” operates as a hindrance to the civilization of a tribe, or that said “medicine-man” resorts to any artifice or device to keep the Indians under his influence or shall adopt any means to prevent the attendance of children at the agency schools.

Indigenous healers and healing practices were viewed as not only an obstacle to the adoption of Christianity but also as an active threat to the boarding school system. These policies were not overturned until the 1934 Wheeler Howard Act and 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act, but the damage to the health of generations of Native communities was already done. The report does point to (and endorse) the NIH-funded Running Bear studies—quantitative medical studies examining the relationship between American Indian boarding school child attendance and physical health status. One of a series of recommendations for moving forward includes the further promotion of Indian health research on the health impacts of the boarding school system.

The Department of the Interior has already launched “The Road to Healing,” a year-long cross-country tour intended “to allow American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian survivors of the federal Indian boarding school system the opportunity to share their stories, help connect communities with trauma-informed support, and facilitate collection of a permanent oral history.”

The report names a few religious organizations who were involved in the boarding school system: the American Missionary Association of the Congregational Church, the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church, the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church, the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, and the Protestant Episcopal Church. There’s now a pressing need for denominations and religious organizations across the US to conduct a transparent examination of their histories and share key records with the Initiative—particularly since such transparency can aid in the further identification of children at these schools.

In addition to transparency about the past, religious groups can work for education and healing in the present. Between 2008 and 2015, Canada organized a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to allow those affected by Indian residential schools to share their stories. Christian organizations, in conjunction with the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, are calling for something similar in the United States. The “Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States Act” has already been introduced in Congress, and this Commission has been endorsed by the Episcopal Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Franciscan Action Network, Friends Committee on National Legislation, the United Methodist Church, Christian Reformed Church of North America, and the Jesuit Conference Office of Justice and Ecology. Some Protestant denominations, such as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) have recently established their own Truth and Healing Councils, even calling for a critical examination of affiliate educational institutions.

Pope Francis recently apologized for the horrendous abuse exacted by the Canadian residential schools, now apologies are needed on behalf of those who suffered within our own borders. The painful task of reckoning with our nation’s history and our religious organizations’ complicity in injustice is a necessary first step to begin addressing intergenerational trauma. Maka Black Elk, executive director of truth and healing for Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, notes that Pope Francis “did something really important, which is name the importance of being indignant at this history.” Surely other religious institutions and organizations can follow suit regarding this unequivocally violent and damaging history.

— Mark M. Lambert (PhD’21) is a postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at the University of Chicago Divinity School and the College. His research focuses on the historical role of religion in shaping public health approaches to leprosy, especially in 19th century Molokai, Hawaii. In the upcoming winter quarter he will be teaching the undergraduate course “Indigenous Religions, Health, and Healing” at the University of Chicago. This article was first published July 7, 2022 in Sightings, a publication of the Martin Marty Center for the Public Understanding of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School, and is reprinted here with permission.