By Chris Caldwell

“He (Howard Thurmond) was 100 years ahead of his time, 50 years ago, so he is still 50 years ahead of you and me.”

Robert A. Hill, Boston University Dean of Marsh Chapel, 2010.

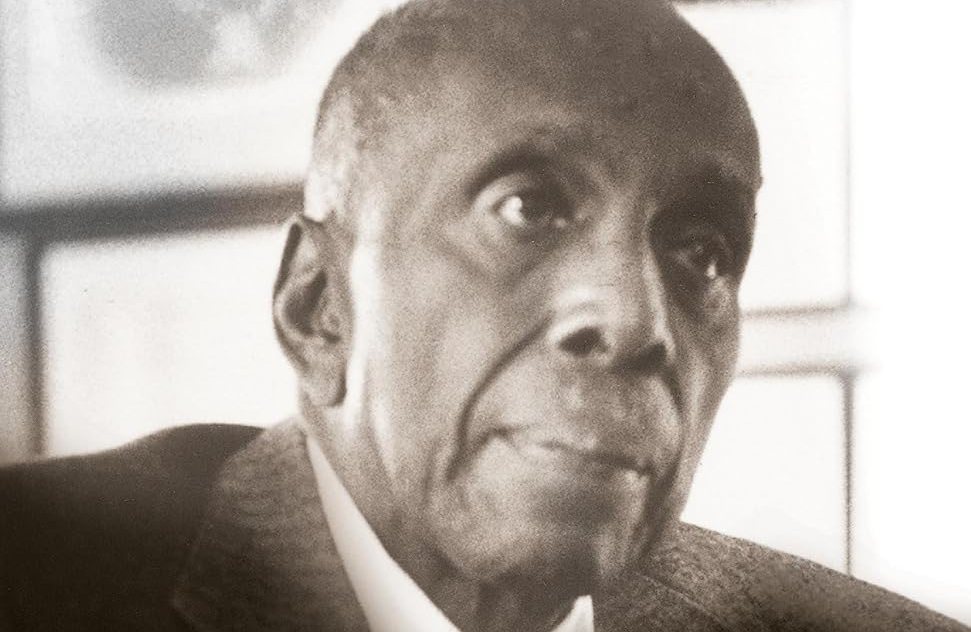

Howard Thurman is justifiably, but I would argue insufficiently, valued as a man whose thinking was ahead of its time. Many do of course know that key parts of what Dr. King said in the 1960s are rooted in what Thurman wrote in the 1940s. Some know that before King famously visited Mahatma Gandhi in 1959, Thurman led a delegation that met with Gandhi in 1935. Thurman was a giant on whose shoulders King stood and, as a result, our nation moved forward.

For this, Thurman has rightfully received the credit due him. But consider all the other ways Thurman was ahead of his time, and consider all the intellectual movements that could have taken place sooner had theologians and biblical scholars focused on the themes in Thurman’s thought that preceded some of our most important advances in theology and biblical interpretation.

Consider these concepts that Thurman put forward ahead of their time in his seminal book, Jesus and the Disinherited, published in 1949.

First, before Paulo Freire and Gustavo Guttierez challenged theology to focus on centuries of Latin American oppression, Thurman wrote:

“I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times that I have heard a sermon on the meaning of religion, of Christianity, to the man who stands with his back against the wall. It is urgent that my meaning be crystal clear. The masses of men live with their backs constantly against the wall. They are the poor, the disinherited, the dispossessed. What does our religion say to them? The issue is not what it counsels them to do for others whose need may be greater, but what religion offers to meet their own needs. The search for an answer to this question is perhaps the most important religious quest of modern life.” (Disinherited, p.3)

Twenty-two years before Guttierez’s A Theology of Liberation was published, Thurman was summarizing the heart of the book.

Second, the 1980s saw a new quest for the historical Jesus in The Jesus Seminar. Two of the most important works that grew out of this movement were Jesus Within Judaism, by E.P. Sanders, and The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, by John Dominic Crossan. Both challenged scholars to take more seriously the influence of Jesus’ first century Jewish context and the way this context was shaped by Roman domination.

A few years later, sociological biblical interpretation looked more closely at how the dynamics and struggles of the ordinary people of Jesus’ day shaped the New Testament. But four decades earlier, Thurman wrote:

“Of course, it may be argued that the fact that Jesus was a Jew is merely coincidental, that God could have expressed himself as easily and effectively in a Roman. True, but the fact is he did not. And it is with that fact that we must deal. The second important fact for our consideration is that Jesus was a poor Jew . . . [and] a member of a minority group in the midst of a larger dominant and controlling group. In 63 BC Palestine fell into the hands of the Romans. After this date the gruesome details of loss of status were etched line by line in the sensitive soul of Israel.” (Disinherited, pp. 7-8)

Third, consider how Thurman argued points that would not yet be at the heart of biblical interpretation for another 40 years. Phyllis Trible’s Texts of Terror and Stephen Moore’s Literary Criticism and the Gospels made the case for reading against the grain of the text and considering how hegemonic forces control the norms of interpretation.

Arguably, Thurman’s grandmother, forbidden to learn to read as an enslaved person, came to this conclusion 100 years earlier. She passed this concept on to Thurman when she forbade him to read to her from the writings of Paul because she had so frequently heard preachers use them to justify her slavery.

Taking this cue from her, Thurman goes on to distinguish between the worldviews of Jesus and Paul, as he argues Paul’s Roman citizenship contributed to some of his least liberative statements (Disinherited, pp. 20-25).

Fourth and finally, the likes of Stanley Fish and Stanley Hauerwas focused on the importance of heeding how our communities affect our interpretations and our theologies. Literary theorists moved from formalism’s “the reader,” to the “implied reader,” and finally to the social locations of real present-day readers.

Thus, over a couple decades, scholars came to see the benefit of trading in neutral, presumably unbiased interpretations, in favor of varied and competing interpretations from those openly allowing their histories and contexts to influence their biblical interpretation. Who knew we could learn so much by reading from our own perspectives and with our communities in mind? Well, Howard Thurman knew it in the 1940s. Again and again in The Disinherited he connects the history of American Blacks, along with their present condition, to the history and conditions Jesus experienced as an oppressed member of a minority group.

Thurman, of course, did not reach such intellectual heights without guides up that mountain. He too “stood on the shoulders of giants”—a phrase I have heard much more often in Black space, with its honoring of ancestors, than I have in white space that honors all things new. DuBois and so many others provided key footholds for him and, to mix my metaphor, in them he drew from roots deep within the Black intellectual tradition. But had King not popularized his ideas, he could easily have lived and died in the obscurity that has been the fate of so many Black theologians, even as he brought forth and applied the best of the African American intellectual tradition.

There is a clever scene in the movie, The Bourne Identity. Jason Bourne lays out an elaborate plan with his girlfriend for her to assist his gaining access to a piece of vital information in a hotel office. Having laid out literally every step she should take to set him up to steal the document, he is surprised to see her return only moments later. She reports she already has the document; when a dumbfounded Bourne asks how she attained it, she replies, “I asked them for it.” “Oh,” he says, “good thinking.”

The guild of white scholars, across a span of decades and generations, has broadened and thereby deepened biblical and theological conversations. We have learned from non-white and non-western scholars who pried their way into the room, and whose insights are now foundational to much of the best and most useful theological and biblical scholarship. But imagine how much more quickly we could have arrived at this destination, had the white scholars of the 1940s and beyond simply taken more seriously Thurman’s works—and indeed the works of so many other Black intellectuals—at the time when they were written.

— Chris Caldwell is on the faculty of the prominent HBCU, Simmons College of Kentucky and directs its Office of Church Engagement.