Resisting Stupidity, Injustice and Complacency: Words of Wisdom and Courage From Confessing Church Pastor Ernst Käsemann

(Photo: Jeremy Segrott from Cardiff, Wales, UK, Wikimedia Commons)

By Cody J. Sanders

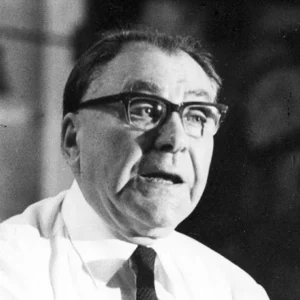

When I, as a Baptist, began teaching at a Lutheran seminary, I started steadily increasing my intake of Lutheran theological voices. In the lead-up to the 2024 election, as well as in the subsequent months, one of my most profound theological influences became Lutheran pastor and theologian, Ernst Käsemann (1906-1998). He’s a figure many New Testament scholars know because of his immense contributions to the academic study of the New Testament — Käsemann’s doctoral supervisor was Rudolf Bultman — but I was hooked by his theological insight for a different reason.

Partially, my intrigue was biographical. Ernst Käsemann longed for order in the 1930s Germany of his young adulthood and thus cast his vote for Adolf Hitler, as many German Protestant ministers of his era did. He soon realized his error but continued to believe that Germany could wait until the next election to correct its mistake of elevating Hitler to office.[1]

Soon, however, Käsemann recognized the urgency of the moment and joined the Pastors’ Emergency League, founded by Martin Niemöller (of “First they came for … and I did not speak out” fame), and they declared the Reich bishop a traitor to the church. Käsemann was denounced as a traitor to Germany and recommended for the concentration camp. On Nov. 15, 1934, in an even more brazen and unprecedented move, Käsemann and colleagues from the Confessing Church publicly dismissed by name 45 Deutsche Christen — supporters of Hitler — from his congregation and presented 45 Confessing Church members — opponents of Hitler — to replace them.[2] In about a year’s time, Käsemann had evolved from voting for Hitler, to realizing his error but waiting for it to resolve itself, to publicly and audaciously opposing the Nazi regime at risk of his own life.

James Cone, father of Black liberation theology, who met Käsemann in 1973, said of him: “Among all the German theologians, or Europeans for that matter, whom I came to know when I began writing, Käsemann was the only one who understood me. He was a man of my own mind and heart.”[3]

Käsemann’s biography is far more extensive than can be rendered here. Unlike martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer — a Käsemann contemporary in the Confessing Church who receives much more attention for his leadership in the Nazi resistance — Käsemann had nearly a half-century of life beyond the Nazi regime. During this time, he reflected on the rise of the Nazis, the captivity of the church to Nazi ideology, the resistance movements, and the warnings that had to be issued again and again to churches on the brink of complicity in great evil. It is out of that context that Käsemann developed his “apocalyptic theology of liberation.”[4]

A Pithy Formulation of Original Sin

While I cannot summarize here the breadth and beauty of Käsemann’s theology, I want to lift up several quotations from his essays and speeches that seem illuminating for contemporary life in the U.S. The first is Käsemann’s definition of “original sin” — a concept with an often-problematic history of interpretation in Christian theology and one liberal Protestants often tend to ignore. In his pithy rendering of the concept, Käsemann stated: “Original sin — which manifests itself in stupidity, injustice and complacency — is not eradicated on earth, according to our faith. But this does not forbid us from denouncing it, opposing it with all our might, and limiting it where possible.”[5]

I find this succinct definition of original sin helpful in pointing to some elements often overlooked in Christian theologizing about sin: stupidity, injustice and complacency. I want to focus not on the stupidity, injustice and complacency of others — though there is much of it — but on our own stupidity, injustice and complacency that imperils our ability to meet the demands of this hour with wisdom and courage. If you run in similar liberal Protestant Christian circles, you might find that this speaks to your experience, too.

Stupidity

In the circles I belong to, stupidity comes in many forms (and I myself participate in it more than I wish to admit). For example, one form of stupidity particular to liberal, highly educated circles is believing that if we have properly diagnosed a problem — i.e., if we’ve thought about the problem correctly — that we’ve somehow done something about it. We parse, we nuance, we define. All of that can be helpful in getting to an actionable theory about what exactly is going on in the world around us — politically, religiously, sociologically — but good theory should lead to praxis, making it possible for us to iterate on our strategies, improving their efficacy when we realize they’re not as effective as we had hoped. Without theory-in-practice, or thought-toward-action, we are left with theoretical theology that never reaches the real world where people live their lives.

If thinking rightly about injustice and violence is where we end — perhaps posting our thinking on social media, but not much else — then we’ve fallen short of genuine engagement that intervenes in the death-dealing practices catching our neighbors in their grips.

Another form of contemporary stupidity suggests that if we can discern which lines surely won’t be crossed — or if we can define just how this historical moment is different from the rise of totalitarianism in Germany or anywhere else — then we can put a little distance between then and now, them and us. But even as we strive to intellectually distance ourselves from the worst horrors of our historical consciousness, that gap is closing quickly.

This larger form of stupidity — the stupidity of the comfortable, we might call it — is evidenced in the belief that it isn’t that bad, or it won’t get that bad, or it’s not likely to continue getting worse for very much longer. This includes the belief — of which we have probably been disabused by now — that the courts will save us or, as Käsemann believed earlier on, that the next election will set things right. This form of stupidity, akin to wishful thinking, occludes the ways that lives are being affected right now in a steady march toward death for those already pressed to the edge vulnerability’s precipitous cliff.

Perhaps the first several months of this administration have shaken you out of these forms of stupidity. Maybe this happened when the president deported 238 Venezuelan men to a maximum-security prison, called a “terrorism confinement center,” in El Salvador, from which, according to the Salvadorian justice minister, the only way out is in a coffin. The men were described as terrorists and violent gang members, yet 75 percent seem to have no criminal record at all.[6] Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the only man returned to the U.S. from that confinement center, has described the severe beatings and psychological torture enacted there: sleep deprivation, being forced to kneel overnight, being denied bathroom access, no windows, bright lights 24 hours a day, etc.[7]

Or perhaps you’ve been shaken awake to the urgency of the moment by the recent creation of “Alligator Alcatraz” in the Florida Everglades. This “one-stop shop to carry out President Trump’s mass deportation agenda” — as Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier has described it — was built in a matter of days to detain 5,000 people and is being operated with FEMA funds designated for emergency disaster relief. “We’d like to see them in many states,” Trump himself said upon visiting the facility. “At some point, they might morph into a system.”[8] Now there’s a line of merch — hats, beer cozies, T-shirts, etc. — that fans of this brutality can purchase to celebrate this cruelty camp in their daily lives.

Injustice

Many years after his involvement in the Nazi-resisting Confessing Church, Käsemann wrote: “We can hide and blind ourselves to injustice, shamefulness and misery. This is happening everywhere in the world today to a degree no less than it once did under the Nazis. And, just as then, it is always happening among Christians.”[9] While injustice is on full display all around us, our own form of Käsemann’s injustice — a form that also must be resisted, denounced, and opposed — lies in the quiet distance we put between ourselves and others whose lives are being ripped apart.

While we might not condone — and may actively condemn — the forms of injustice we see taking shape, the more psychological distance we can put between the victims of our contemporary political death machine and ourselves, the wider we make the empathy gap. A lack of empathy is the fuel complacency needs to grow. This is where the recent conservative Christian attack on empathy becomes most dangerous.[10]

Sometimes it’s cognitive normalcy bias that creates the empathy-sapping psychological distance that leads us to believe that things can’t be as bad — or get as bad — as some make out. So, we underreact to the unfolding horrors until it’s too late. This normalcy bias manifests itself as a niggling doubt, so easily summoned, that suggests maybe they did something to deserve this, and that good people who follow the rules — like us! — will be just fine. It’s a sentiment that was alive and in full force in the church of Käsemann’s Germany.

All of it, nevertheless, leads to our own enablement of the injustices taking shape around us, sending our neighbors to camps in which many will die.

Complacency

As it turns out, of the three components of Käsemann’s tripartite definition of original sin, complacency is the easiest to spot among us. [11] Like original sin, complacency can arrive in several forms; I’ve seen Christians use their faith to distance themselves from political realities in a few specific and repeated ways. First, we use the fear of mixing faith and politics to rationalize our inaction, conveniently defining “politics” so broadly that it comes to mean the systems and structures responsible for the very destruction of our neighbors’ lives. At the same time, we let our fear of edging too close to “works righteousness” cloud our call to acts of solidarity and service with our neighbors. In some cases, we rely on theologies so otherworldly that we, as contemporary Christians, have a hard time imagining what the call of discipleship looks like now, in the flesh, in solidarity with our neighbors. Käsemann addressed these forms of complacency, saying:

It appears to me to be a monstrous perversion when the gospel and confession are invoked and misused in order to be removed from the world of the abused and enslaved, to abandon them to their rulers, undisturbed by the horror of the victims, to seek after personal earthly and heavenly bliss … Those who want to watch their backs, who refuse to dirty their hands, and who cowardly seek to guard themselves form trouble cannot be their brothers’ keepers, cannot advocate for what is human, cannot be servants of the Crucified. That is clear and simple to pronounce today.[12]

Friends, we cannot follow Christ and hold to the belief that the practice of our faith has nothing to do with the suffering of others or the unjust relations of society! That is heresy for those who claim to follow a crucified God risen in power over the death-dealing machinations of empire. As Käsemann put it, the church “is legitimately such only in the shadow of his cross … For the people of God on earth are the multitude of those who are only allowed to wear the cross on their chests if they have previously carried it on their backs.”[13]

Readers who wish to engage more with the work of Ernst Käsemann should consult his many reflections — very relevant for contemporary Christians — on the German church’s experience of Nazi complicity and resistance. In addition to the source cited in this article, other places to begin are his book Jesus Means Freedom (1968) and a collection of addresses and essays titled On Being a Disciple of the Crucified Nazarene (2010). At this point in our history, time spent immersed in the words and wisdom of Käsemann will be well spent, and — if your reaction is anything like mine — will prove courage-inducing for those seeking to follow the ways of Jesus amid the stupidity, injustice and complacency we face in our current era of cruelty.

— Cody J. Sanders is Associate Professor of Congregational and Community Care Leadership at Luther Seminary, Saint Paul, MN. An ordained Baptist minister, he is the author of several books and serves on the CET board.

_________________________________________

[1] Ry O. Siggelkow, “Editor’s Introduction,” in Ernst Käsemann, Church Conflicts: The Cross, Apocalyptic, and Political Resistance, ed. Ry. O. Sigglkow, trans. Roy A. Harrisville (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2021), xi. Emphasis original.

[2] Siggelkow, “Editor’s Introduction,” xi-xiii.

[3] James H. Cone, “Foreword,” in Ernst Käsemann, Church Conflicts: The Cross, Apocalyptic, and Political Resistance, ed. Ry. O. Sigglkow, trans. Roy A. Harrisville (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2021), viii.

[4] Siggelkow, “Editor’s Introduction,” x. Emphasis original.

[5] Ernst Käsemann, Church Conflicts: The Cross, Apocalyptic, and Political Resistance, ed. Ry. O. Sigglkow, trans. Roy A. Harrisville (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2021), 138-9.

[6] Cecilia Vega, “U.S. Sent 238 Migrants to Salvadoran Mega-Prison; Documents Indicated Most Have No Apparent Criminal Records,” CBS News, April 6, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/what-records-show-about-migrants-sent-to-salvadoran-prison-60-minutes-transcript/.

[7] Josh Gerstein and Kyle Cheney, “Kilmar Abrego Garcia Describes ‘Severe Beatings’ and ‘Psychological Torture’ in Salvadoran Prison,” Politico, July 2, 2025, https://www.politico.com/news/2025/07/02/kilmar-abrego-garcia-salvadoran-prison-account-00438153?fbclid=IwQ0xDSwLTZ4BleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHsISQh1QmG2-kosGsLfDECHeT-ZTamblM48HbTmWU8Rc2zfNrhLG1vgOZ2L9_aem_EmMk01Cx62lxC6vkckxxhw.

[8] Inae Oh, “The Cartoonish Cruelty of Trump’s Alligator Alcatraz,” Mother Jones, July 1, 2025, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2025/07/alligator-alcatraz-trump/.

[9] Käsemann, Church Conflicts, 159.

[10] Rodney Kennedy, “Why Empathy is Under Assault Today,” Baptist News Global, March 11, 2025, https://baptistnews.com/article/why-empathy-is-under-assault-today/.

[11] Importantly, I don’t want to confuse “complacency” with the communal trauma response of simply being so overwhelmed that we don’t know what to do…yet. That has been true for many of us trying to figure out what our work is in this moment and how we can band together to take action on the call to do something. Complacency, by contrast, rationalizes away our need to do anything at all.

[12] Käsemann, Church Conflicts, 160-61.

[13] Käsemann, Church Conflicts, 3, 13.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.