A Cross-Cultural Ethics of Bible Translation

By Kristofer Dake Phan Coffman

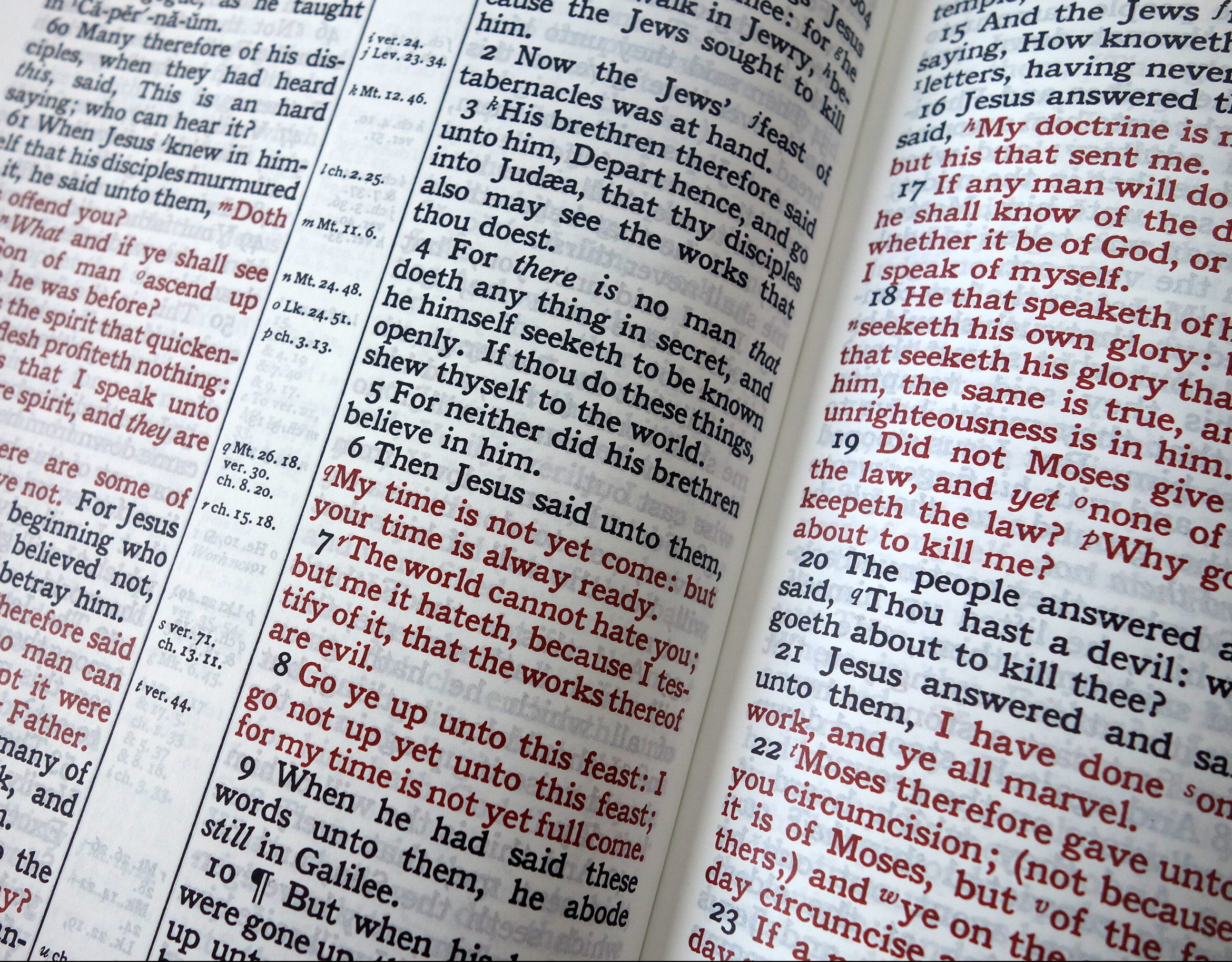

“To translate is to betray” is an Italian aphorism that biblical translators like to cite when introducing the difficulties of rendering ancient Hebrew and Greek into modern languages. The aphorism illustrates its own point, as the English rendering betrays both the brevity and the pun in the Italian, “traduttore, traditore,” literally “translator, traitor.” In their aphorism the Italians have encapsulated not only a linguistic, but also a historical observation, both of which have ramifications for the ethics of translating the Bible. As the skepticism in the aphorism alludes to, most discussions of Bible translation focus on a cautionary ethics, and it’s there where we will also begin.

Reticence around translating scriptures has roots that reach back into antiquity. Folks in the western world may be familiar with the fact that both Judaism and Islam have branches that reject the translation of the Torah and the Qur’an on the grounds that a translation cannot capture the meaning of the original Hebrew or Arabic. This rejection of translation extends beyond the Abrahamic religions. In the Cambodian Buddhism in which my mother grew up, monks continue to chant sacred texts in Sanskrit and Pali rather than in Cambodian. Even when translations were made, their approval required special pleading.

The Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible known as the Septuagint presents an illustrative case. Greek speaking Judeans in the Diaspora needed a Bible that they could understand, but skepticism about the viability of translating from Hebrew into Greek led to the rise of the myth of the 72 elders. According to myth, recorded in the Letter of Aristeas and repeated by Philo of Alexandria, the Egyptian King Ptolemy II wanted a Greek copy of the Hebrew scriptures for his library. He assembled 72 elders (six from each of the 12 tribes of Israel) and placed them in separate rooms to do individual translations. When they brought their copies to them, they were all identical, proving that the translation had a divine provenance.

In the early 20th century, the incommensurability of languages became formalized in the linguistic theory of Ferdinand de Saussure. Saussure’s linguistics distinguished between the signifier (the word that we use to refer to something) and the signified (the actual thing to which we are referring) and noted that the connection between the two is psychological, i.e. the signifier calls up an association in our minds. Because no two minds are alike, no two people will call up the same association even if using the same word. This concept applies with double force to signifiers in different languages. Even if the signified thing is the same, when two different languages describe it, they will inevitably call up mental associations based on the history and the culture of the respective languages. The end result of this linguistic theorizing is that it reframes translation. The translator no longer looks for equivalents between words, but instead tries to “draw” a Venn diagram in which the associations of a word in one language overlap as much as possible with a word in another.

Recognizing the impossibility of 1:1 translation raises a number of ethical concerns for the biblical translator. For one, the translator must be conscious of how they domesticate a biblical text. A translator domesticates a text when they choose terms that are familiar to their intended audience but which only loosely correspond to the original. For example, in Amos 5:24, the NRSV translates, “Instead let justice flow like a stream, and righteousness like a river that never goes dry.” The Hebrew word translate “river” is nachal and it refers to an intermittent desert stream that flows during periods of rain, but is otherwise dry. In Arabic, they call it a wadi and those of us who grew up in the American Southwest borrow the Spanish word, arroyo, but there is no English equivalent. The word “river,” in fact, calls up a totally different association for most English speakers. This kind of domestication raises the concern of whether the translator misleads their readers through making the text too familiar. If, as for many Americans, the 23rd Psalm calls up associations with verdant English pastures, has the translator done a disservice to their readers?

Beyond the problem of domestication lies the reality that the lack of 1:1 equivalents between words means that the translator exerts personal influence on a translation. They cannot simply be thought of as an algorithm or a machine that with sufficient training transforms one language into another. Instead, a biblical translator makes innumerable choices regarding how to express the text in English, choices that are informed by their own life stories, their own theology, and their own ear for how the English language should sound. One of the great ethical missteps of modern Bible translation is the way in which translation committees obfuscate the role of the translator. This is especially problematic in translations like the NRSV which pride themselves on their scholarly credentials; scholarship (as those of us involved in it know too well), is an inherently contested and ever-changing field. Knowing the identity and background of a scholar is an essential part of understanding the choices that they have made.

As important as these cautionary ethical considerations are and, as much as I hope that all biblical translators will be aware of them, I don’t believe that they tell the whole story. From my perspective as a first-generation Cambodian(American), this approach to biblical translation, though scientific and scholarly, presents too static a picture to capture the ethical responsibilities of the translator.[1] As someone who has spent his life moving in different cultural and linguistic spaces, I believe that biblical translation can learn from the considerations of those of us who have to translate in real time. The reconsideration of translation through the first-generation experience has led me to reframe translating the Bible in terms of an ethics of care. This reframing changes the role of translator; rather than acting as the expert who transforms knowledge for the consumption of the uninitiated, the translator stands as a mediator between two conversation partners.

People come to the Bible with questions and hopes and fears. The biblical text comes with messages to speak into our realities. The translator stands between them, hears them both, and crafts their translation accordingly. This approach moves beyond the myth that we can draw a neat line between “translating” and “interpreting.” All translation is interpretation and what matters is whether we have the courage to admit our role in that interpretation or not. The translator becomes a traitor when they fail to care for the participants in the conversation, and this duty of care runs both ways. On the one hand, a translation that willfully twists the biblical text betrays it. On the other, a translation that comes written at a level so educated or so formal that it is unintelligible to a congregation is also traitorous.

The great difficulty of thinking of translation in terms of an ethic of care is how few hard and fast rules there are. When I introduce this way of thinking to my students (most of whom are English monolinguals), the result is often a paralyzing fear: How can we dare to translate if we will inevitably get things wrong? The answer that I give, though unscientific, is to follow the advice of Martin Luther and “Sin boldly, but believe more boldly still!” The burden lies on us as translators to do our best, to show our cards and to acknowledge that we will inevitably betray one side or the other. Further, I remind them that this ethic requires thinking of translation as an ongoing conversation. This conversation involves confession of our errors and forgiveness and working to continually explain ourselves. Most of all, it’s a conversation conditioned by love—love for the biblical text and love for the people who come to it seeking admonition and comfort.

Those of us who are first-generation Americans know that one of the profound paradoxes of our lives is that we will never speak our mother tongues, our heart languages, with one or more of our parents. When I speak English with my mother, it is her second language. When she speaks Cambodian to me, it is my second language. Something will always be lost in translation, but the bond between us overcomes that linguistic gap. I trust that the Holy Spirit will do the same with our translations of the Bible, bridging that gap between the ancient and the modern so that we can faithfully say “traduttore, non traditore” [translator, not traitor!].

— Kristofer Phan Coffman is assistant professor of New Testament at Luther Seminary. He brings his own experience as a first-generation Cambodian-American to his readings of the biblical text in an effort to help readers reframe their reading of ancient texts as a cross-cultural interaction, hoping to build skills both for the reading of the biblical text as well as the modern task of relating to people from cultures different than their own.

__________________________________

[1] There is considerable confusion regarding generational terminology in the United States. While I am a first-generation American, by U.S. Census standards, I am a second-generation immigrant. By sociological definition, I am a 2.5-generation immigrant, meaning that I have one parent born outside the U.S. and one parent born in the U.S. As many have pointed out, the term “second-generation immigrant” is an oxymoron, which is why I prefer to refer to myself as a first-generation Cambodian(American).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.