Applying Christian Wisdom

By George A. Mason

When my daughter and son-in-law graduated from divinity school, my wife and I commissioned an artist to paint two complementary works that would depict Word and Wisdom — roughly correlating to the two different sources their ministries would draw from. The artist created one painting of a mountain and the other of a stream. They hang side-by-side now in their living room, just as they should always be side-by-side in the pursuit of knowledge.

Christianity, like Judaism and Islam, draws upon the revelation of the word of God that comes down to us. Moses receiving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai is the paradigm of this approach to religious knowledge. But alongside the word that drops into history and human consciousness is the wisdom that springs up from nature itself. As the Franciscan spiritual teacher, Richard Rohr, likes to say, “Nature was our first Bible.” That is, before any word from God fell upon the ears of prophets, the wordless creation of God made itself known to us.

When the last of the four Gospel accounts of Jesus was written, it had become important to relate the human Jesus to the eternal life and work of God from creation onward, including ways people outside the faith had apprehended truth. The writer draws on the link in Judaism between word and wisdom and joins it to the language of Greek philosophy.

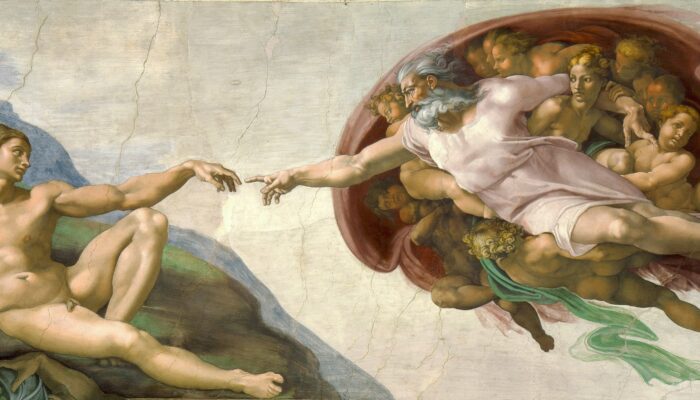

The early church theologian, Irenaeus of Lyon, spoke of God’s two hands in creation: namely, word and wisdom. If the word brought the world into being, wisdom gave it shape and meaning. The primacy of the word that gives rise to the Law in Judaism and the gospel in Christianity is understandable, but that does not exclude the role of wisdom. As Proverbs 8 puts it, “The Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts long ago.” Then it continues by speaking of how wisdom carefully set up all the relationships that make up the harmony of creation. Wisdom is built into reality itself and reality itself can be known by it.

Despite the prominence of the word as revelation, ultimately, the Bible is a book of wisdom — less a rulebook than a guidebook. And even when it seems to be a rulebook, those rules are intended to be a guide to what 1 Timothy calls “the life that really is life.”

Now, the Bible is chiefly a record of God’s redemptive work with humans. Nature tends to be treated more as the backdrop to the human story. But there are glimpses of how these cannot be separated.

For instance, the creation stories in Genesis begin with nature first. In the first story (which is likely the second in time), humans are the crowning achievement of creation. It takes six days to get to us, which is to say we are dependent for our existence on the rest of nature that preceded us. This is confirmed, of course, by evolutionary theory. Humans share 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees. The second and oldest account, shows the Earth Man — adam — being formed out of the dust of the ground and only becoming a living being upon the vitalizing breath of God breathed into his nostrils.

All of which is to say, that the story of humankind is not and cannot be told apart from the natural world. We are spirit and stuff, never one without the other. And whatever our human future, it will be tied to the future of the nonhuman world.

We see in the Hebrew Bible how often judgment for human sin is reflected in natural disasters: the curse of the ground in Eden, famines, droughts, floods, storms, and even brimstone. But we also see where nature proclaims the glory of God, how the mountains and the hills sing for joy the trees of the fields clap their hands. The poet told us something by metaphor of the living character of nature before we came to understand the ways trees communicate with one another and all of life is connected through DNA—human and nonhuman alike.

The early church was not uniform in its appreciation of the role of wisdom. Tertullian famously asked, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” But others, like Justin Martyr, saw the deeper connection. The logos of God is the combination of word and wisdom—sophia, then the world is both rational in the way it is ordered and understandable at the same time. He posited that the Logos finds its complement in the logos spermatikos, the rational capacity that resides within every human being. This opens the door to human reason and scientific pursuit.

The theologian and missiologist, Leslie Newbigin, proffered that Christianity—and I would say Judaism too in its own way—provides the necessary groundwork for science in that it deems the created world both rational and contingent. That is, nature is dependable and understandable in principle, and it is free and open. The freedom of creation is seen positively in its ability to adapt and change across time and negatively in the chaos that threatens its stability at every turn.

All of this is to say that there are adequate grounds within the Christian faith for a productive conversation and partnership with science. The church hasn’t always seen the scientific method as compatible with faith. Galileo’s heliocentric universe seemed a threat to the church’s authority over all learning that derived from its reading of the Bible. Likewise, Darwin’s theory of evolution and Hawkings’ notion of the eternality of space-time has caused concern, to say the least. And today, much of the skepticism toward science regrettably comes from Christianity.

Science, for its part, can devolve into scientism. That is, it can become a totalistic epistemology that makes no room for the divine and no place for religion to contribute to a fuller conception of reality than science can muster on its own. However, religion could be a productive partner with science in addressing global ills. One of those ills being the topic of this evening—our worldwide ecological crisis.

Religion can and should give confidence to people to trust that truth is truth wherever and however it is found — whether by revelation of the word of God that comes by hearing, or by discovery of the wisdom of God that comes by seeing. Science works by observation of creation. It is not a natural enemy of religion; it is a partner to it. Science works from below, so to speak, while religion works from above. One works inductively, while the other deductively. Both build models of knowledge — one called faith and the other hypothesis, and then each adjusts the models in the light of testing in their respective laboratories.

I should stipulate that there is more than one form of Christianity, and not every version is as amenable to my description of things. One Christianity today is particularly hostile to attempts to address global warming, climate change and all its effects on the planet. In this version, efforts to care for creation distract true believers from their duty to save souls. I actually had a woman tell me once that recycling efforts we were encouraging in our church were the way the devil-inspired New Age Movement was slipping into the church. According to this view of things, the Earth will be destroyed in the last days and only those humans who are true believers in Jesus will be saved. And how they will be saved is by escaping their bodies and going to Heaven, leaving Earth behind. Therefore, all efforts at ecological conservation are futile.

Furthermore, God made it plain in Genesis, they think, that humans are to have dominion over the earth. Which they wrongly—in my view—understand to mean that nature is there to serve us rather than our being charged to serve nature in helping it to achieve its divine purpose of flourishing as our habitat.

The Bible is not plain. It must always be interpreted. Wisdom is found in choosing those parts that comport best with an overall vision of creation and redemption, and then treating other parts in light of it.

In his letter to the Romans, St. Paul sees hope for nonhuman creation. He declares that creation itself longs to be free from its bondage to decay and will at last in the end obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. This is a far cry from the apocalyptic passages that see the Earth burning up in a climatic conflagration. In Paul’s view, human and nonhuman nature both depend upon God for our redemption, but nonhuman redemption leans on humans for its hope.

It’s past time for religion to join science in partnership for the preservation of the planet. Theology has to join anthropology with ecology in a more holistic approach.

That will require more spiritual humility than we often exhibit. We have to acknowledge that we don’t have all the answers to all the questions all the time. God has chosen to embed the truth in creation that awaits our discovery of it. This requires respect for scientific inquiry and patience for the possibility of new understanding. But what I have been trying to say in this presentation is that we have even within our Christian scriptures and tradition a lightly beaten path to follow. So much is at stake.John Philip Newell writes in his book Christ and the Celts: “At the end of my talk [focused on John 1:9], a Mohawk elder, who had been invited to comment on the common ground between Celtic spirituality and the native spirituality of his people, stood with tears in his eyes. He said,

‘As I have listened to these themes, I have been wondering where I would be today. I have been wondering where my people would be today. And I have been wondering where we would be as a Western world today if the mission that came to us from Europe centuries ago had come expecting to find Light in us.’”

It’s time to find the Light in Native American spirituality that gives primacy to the Earth as our common Mother and to science that investigates the Earth for ways to preserve it. This is the path of wisdom that Christianity must begin to follow.

— George A. Mason is Pastor Emeritus of Wilshire Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas. He currently serves as Chairman of the Board of Christian Ethics Today Foundation, is host of the weekly podcast, Good God, and is very widely regarded as a pastor, theologian, speaker, writer, and advocate for progressive Christian living. This paper was first delivered at the Global Ecological Summit at Southern Methodist University on November 1, 2022, and is reprinted here with permission of the author.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.