Bowing Down to the Bramble: Parables, Politics, Perils, and Perseverance

By Allan Boesak

As we are about to enter the thirtieth year of our democratic experiment, I believe South Africans have much to learn from the Book of Judges in the Bible. Looking around the globe today though, so, actually, have the rest of the world. To help us think through some of the most daunting issues facing South Africa, and the global community today that I will be pondering in the essays in this volume, I begin this collection of political and spiritual reflections with a meditative look at this most fascinating book.

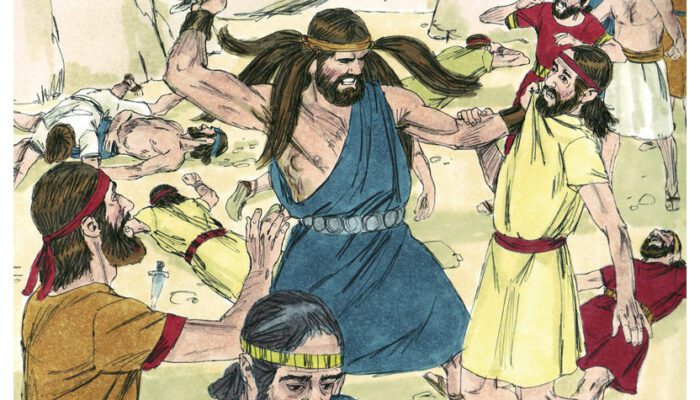

Judges is a book in which ancient Israel tells its stories about extraordinary men and women in calamitous times, times of great difficulty and strife. It is a book about struggles against oppression and about the leaders and icons of those struggles, heroes of the people. South Africans know about those struggles and those who led us in them over the centuries past. “Judges” were not arbiters of legal disputes, as we know them in our courts today, or even in the courts of ancient Israelite society. Nor were they rulers. The title of the book in the Afrikaans Bible, “Rigters” – persons giving direction to the people in times of need – may perhaps give a better sense of what ancient Israel had in mind. They were brilliant, charismatic leaders, men and women of great courage, and, crucially, from among the people, called by God and chosen by the people to lead them in their fights for freedom and their wars of liberation and independence. “Then Yahweh raised up judges who delivered them out of the power of those who plundered them.” (2:16) Note the connection between the three key words here, “power”, “deliver”, and “plunder”. Today, following Antonio Gramschi, we would call them “organic” leaders. We have had quite a few of those. Like us, Judges is not shy to celebrate the role women played in those struggles. War is a constant presence in these stories and consequently, from the first pages to the last, Judges is a disturbingly violent book.

Tellingly however, Judges does not have the strident, triumphalist tones that we find in the Book of Joshua. Joshua tells the story of ancient Israel’s violent conquest of ancient Palestine (Canaan) and it is a triumphant blitzkrieg. Israel’s military might is unstoppable. No nation remains standing before it. The author seems to revel in the endless bloodletting and the brutal abandon with which cities, humans and animals are destroyed. That tone is missing in Judges. In fact, I find that in Judges, the stories about war and violence have a deeply tragic tinge about them.

Judges begins by telling us that the Joshua story of a complete, triumphant conquest of Canaan, though beloved, is not correct. Israel had failed in this quest, hence the constant, never-ending wars led by the judges, against the people of Canaan, the indigenous people of the land. That kind of honesty is hard to come by. Sometimes our politicians talk as if the struggle against apartheid and neo-colonialism is over, that apartheid in all its forms had been overcome by a new dawn, and we still act as if that “victory” was celebrated by our tanks rolling through the streets of Pretoria, the “amandlas!” and “vivas!” bouncing off the walls of the Union Buildings. Every January 8, celebrating the birthday of the African National Congress, we listen to, and revel in the triumphant speeches. We dance and sing and toyi-toyi, hoping that the loudness of our songs and slogans will be able to drown out the reality that the real revolution was stolen and replaced by a political capitulation concocted by the elites of the old, white, apartheid capitalist class, and sealed with the compliance of our new political aristocracy.

The truth is that we are in serious battle with the consequences of an incomplete revolution, an incomplete reconciliation, and an incomplete restoration. We are still in a struggle to find the true meaning of freedom, and how to face the responsibilities and challenges that come with freedom. But that kind of truthfulness is a minefield where politics rarely wants to go. In Selfless Revolutionaries, I devote a full chapter to a discussion on the question of our incomplete revolution.

The writers of the early chapters of Judges apparently decided that telling the truth, even though it is hard, shows respect for the people, their memories, and their sacrifices. That telling begins with the very first words of the very first chapter and grapples with that painful truth until, in chapter 3, the author finally finds a way to explain away the failures, and it is, as so often is the case with religious people, theological: “Now these are the nations that the LORD left [in Canaan].” (My emphasis) It is God’s doing, in other words, and here’s why: Yahweh did it to “test all those in Israel who had no experience of any war in Canaan” (v.2). The author is speaking of those who had come, were welcomed, and for successive generations, had lived peacefully with the original inhabitants of the land. To replace the presence of peace with the necessity of war becomes a test of Israel’s faithfulness and obedience to God. “Obedience” to God does not mean making friends and neighbours out of those we term “enemies” and learning to live together in a world we must all share. Obedience is first making sure that for us they are eternal enemies, and then exterminating those enemies to the last man, woman, and child; attacking and razing their cities to the ground, taking possession of them, renaming them, and living in them as if the former inhabitants never existed. All the while, of course, giving praise to God’s goodness for allowing us to do this, fulfilling God’s will, and solidifying our power and dominance.

Yet, the remnants of the glorification of war are hard to let go of, and so are the shreds of glory clinging to the old conquest stories, even if these were not completely true. However, now committed, the author has to double down on the twisted theological logic. So the author continues, still in verse 1, “It was only that successive generations might know war, to teach those who had no experience of it before …” (3:1, 2). See immediately here a dilemma that Judges does not even attempt to solve. If the author had said that some nations in Canaan were friendly and hospitable, and had accepted the new comers, but that the kings of some of the other nations had ambitions of domination, and would not let Israel “rest”, but attacked and oppressed them, and that therefore, Israel had to defend its new-found freedom, that would offer a different perspective. Determined not to be taken back to the days of slavery they had experienced in Egypt, Israel’s defensive violence would be perfectly understandable.

With that in mind, chapter 2:16, quoted above, would make immediate sense: Israel was under attack, sometimes overrun and oppressed, and in such times Yahweh raised up judges to defend the people’s right to freedom. Then this would have been a different story. This also, would be in line with what well-respected Hebrew Bible scholars George Mendenhall and Norman Gottwald had proposed, namely that these fights were not offensive battles in wars of conquest waged by the Israelites. They were struggles against oppression and domination. This is not Joshua’s wars of aggression and conquest. This would be Israel, defending its liberation against new oppressors in the new land where they had settled.

However, the text does not say that. Accordingly, the strangeness of the theological logic deepens. Yahweh does not only want to “test” the new generation’s willingness to go to war, Yahweh actually wants to “teach” them how to make war. Never mind Isaiah’s fervent wish that swords be turned into ploughshares and spears into pruning hooks; and never mind Yahweh’s intention that never again shall “nation lift up sword against nation, and neither shall they learn to make war anymore.” (Is. 2:4) All that idealistic, unrealistic talk has no place here. Yahweh’s desire is not for peace and harmony with the peoples of the land, but for Israel’s younger generation to learn how to make war. God really wants that total destruction, that total land theft, the total annihilation of Canaan’s people.

It is a theological trend of thought that we will find regularly in what Hebrew Bible scholar Walter Brueggemann has called the “royal theology trajectory” in the Bible. In other words, the theology of the establishment, of the mighty and the powerful. It is a theology of violence, of unbridled, chauvinistic, religious nationalism. It would be in serious tension with what he identifies as the “prophetic theology trajectory,” which seeks to give voice to the people’s faith in Yahweh as a God of justice, peace, and steadfast love.

And not only had the conquest failed, the Canaanites seemed to have won the hearts and minds of Israel’s new generations: “So the Israelites lived among the Canaanites … and they took their daughters as wives for themselves, and their own daughters they gave to their sons …” And then the author adds the final blow: “And they worshipped their gods” (3:6). The tragedy seems complete. But which is the greater tragedy? That the Israelites had lived in peace with the Canaanites, and that, consequently, they did not “know war” anymore? That they intermarried, or that they worshipped the strange gods of the Canaanites?

II

For me the Book of Judges is not so much about the failures of single persons, heroes who disappoint, charismatic leaders who let God and the people down, sometimes becoming the personification of the people’s failure to believe, to have faith and trust in God, to stay faithful to God – their overreach and hubris, forgetting their dependence upon Yahweh. For me, the overriding issue, and in a sense the real message of the book, is the exposure of the failure of violence as solution to political and social questions and challenges. What may read as glorification of violence, I hear as a hundred alarm bells clanging on every page. The tragedy in Judges is not that the heroes failed the people, or that military victories were so scarce and those that did come about, were so fleeting, not really able to bring the lasting and sustainable peace the people sought. The tragedy is violence, all by itself, its fatal lure, its seductive power, and Israel’s embrace of it. The tragedy is to discover just how far ancient Israel has strayed from the spirit of the Song of Miriam in Exodus 15. Every military victory ends with the announcement of the period Israel had “rest”. After Othniel, forty years; after Ehud eighty years; after Deborah again only forty years.

It sounds like us. After Mandela, what? Five years, perhaps not even, for have we not had the violence of perpetuated impoverishment, hunger, empty and broken promises, of political banditry at the highest levels since the “new era” began? And as a result, have we not had what we euphemistically called service delivery protests across the country every other week, it seems? In the euphoric days, when our people still believed we had hope of some kind, before we began to really see the consequences of the secret deals and the elite pacts, taste the bitter fruits of our pre-negotiated negotiations? And now, standing as we do among the ruins of our ideals and aspirations, hopes and dreams forged in the fires of centuries of struggle, our thirty years of democratic endeavour, filled with strife caused by purposeful neglect, unprincipled politics, mind boggling corruption and visionless leadership, we are uncomfortably close to the “forty years” refrain from Judges. Is this what a pre-determined, and willingly chosen, downfall looks like?

After someone called Shamgar, the years of “rest” are not even mentioned. His whole life reads like a footnote bordering on what I imagine as an indifferent shrug of the shoulders: “After [Ehud] came Shamgar son of Anath … He killed six hundred Philistines.” That is all there is to say in the single verse that mentions this leader of Israel. The killings made no difference it seems. The author seems almost dismissive: “He too delivered Israel.” (3:31) Samson’s death, like that of a modern suicide bomber, in fact his whole life dedicated to struggle, four whole chapters of stories, failings as well as heroics, is summed up in just seventeen words: “So those he killed at his death were more than those he had killed during his life.” (16:30b)

Contrast these words with the words of the prophet Elisha in II Kings 6. There the armies of the Arameans have surrounded Israel. They are stationed across the hills in their thousands. Elisha’s servant panics. “What shall we do?” To this the prophet responds, “Do not be afraid. Those who are with us, are more than those who are with them” (v.16) On the lips of the prophet, the “more” does not refer to killings and slaughter. Neither do they refer to the armies of Israel’s king. For Elisha, that “more” is the presence, the faithfulness, the trustworthiness of Yahweh. What follows is what most scholars describe as a myth, and some as a miracle. Upon Elisha’s prayer, the Aramean army is struck with blindness, is led to a different city, where their eyes are again opened.

The point, however, is not whether this is a myth or a miracle. The point is in what follows, in the lessons the Bible is trying to teach us. When the king of Israel sees what is happening, and that he basically has the enemy army, confused and disorientated, at his mercy, his first instinct is to grab the opportunity for glory: he wants to annihilate them. The twice repeated “Shall I kill them?” shows the nauseating eagerness for glory soaked in blood. Perhaps the king was just a plain old warmonger. Perhaps he was thinking of his shares in the weapons industry; or perhaps his domestic ratings were so worryingly low he reckoned that only his heroics in war could bring him favour with the people.

But in Samaria, Elijah is more in tune with God than was his mentor Elijah, on Mount Carmel. War is not the answer. He is firm: “No! Set food and water before them, so that they may eat and drink; and let them go to their master. So he prepared for them a great feast …” (v.22, 23a). The true prophet of God abhors the violence, does not revel in bloodshed, has no thirst for brutality, does not seek the vainglory of war. What Elisha accomplishes is a victory for diplomacy and nonviolence of epic proportions. Where are the prophets of God who would give such wise counsel to the Bidens and the Putins of our world? And if Cyril Ramaphosa had the counsel of true prophets of God, would the tragedy of the Marikana massacre have happened? Lessons, lessons, lessons.

But let us go back to Judges, Shamgar, and his six hundred killings. Even after all that, the hoped-for deliverance did not come. It is, after all is said and done, ineffably sad. From there, it’s all downhill. And it is also from this point on, in chapter 18, that we begin to hear the refrain, “And in those days there was no king in Israel”, soon to be followed by the words that had come to complete the sentence, “Everyone did what was right in their own eyes.”

The durable peace Israel was seeking was not an unattainable dream, a mirage, the idealistic chatter of a few romantic populists, however, and Judges acknowledges it. In that same chapter 18, we are told how the tribe of Dan, still on a campaign of aggressive expansion and land theft (what Hitler would call the campaign for lebensraum), attacked another city called Laish. They set upon the people, “a people quiet and unsuspecting” the writer says twice, “put them all to the sword, and burnt down the city” (18:27). By now, these scenes are depressingly familiar. But they are familiar for another reason.

They remind us so much of what the State of Israel has been doing to Palestinians and their land for over seventy years, it is downright scary. The aggression with which that theft is taking place, making way for new Israeli settlers at a breath taking pace, the way the violence is normalised, executed as a matter of course, and with an impunity just as natural. No big deal: it’s just “putting facts on the ground”, as Benyamin Netanyahu has stated, and every politician understands that. That Palestinians are systematically dispossessed, disowned, displaced, and disinherited? No matter, that’s the way of the politics of the bramble. Get used to it, get with it, or get out of the way.

But the point I want to make here does not lie in the “natural flow” of war, land theft and destruction as depicted in Judges. Tucked away in the middle of this tale, so that it almost always goes unnoticed, in verse 7, we are told what the five Danites discover as they do their reconnaissance of the area. They saw, Judges tells us, a very desirable stretch of land, “a broad land”, fertile and rich, inhabited by people living there “securely … quiet and unsuspecting, lacking nothing on earth, and possessing wealth.” Laish was a peaceful city, hence a secure city, hence a prosperous people. They actually existed, totally disproving and discrediting the perverse logic and the dominant narratives of the warmongers, that it is war and dispossession of others that bring peace and security.

As soon as the men from Dan saw the beauty and richness of the land, they just knew it was God’s will for them to claim it for themselves. In their hearts and minds, their God always walks hand in hand with greed, the lust for acquisitiveness, and dominion. Upon seeing so prosperous a land, such wealth, and so peaceful and unsuspecting a people, they drool at the sight, and so does their God. They say to themselves what those Christian imperialist invaders from Holland and Britain said when they saw the beauty and bounty of this corner of Africa: “The land is broad – God has surely given it into [our] hands – a place where there is no lack of anything on earth” (v 10).

The author’s choice of words is revealing. The people of Laish are prosperous, “living securely”. That is because, unlike so many around them, they are not a warlike people. If one is perpetually at war, all one’s resources go towards the war. There is no money, or time, or inclination left for the necessary things, such as infrastructure, agriculture, or the pursuit of the things that make for peace. War does not allow for the cultivation of olive trees, fig trees or for the vine to ripen and produce wine. That wonderful vision seen by the prophet Micah, that “They will all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees, and no one shall make them afraid” (4:4), is a vision of peace that is impossible for a war-like people with a war economy, and a war-mongering mind set. It is impossible for a people living in constant fear that what we “are doing over there”, will someday be done to us “over here”. American scholar of politics Chalmers Johnson, in his searing analyses of the workings of American empire, called it “blowback.” Preacher/prophet Dr. Jeremiah Wright, in one of the most stunning sermons I have ever heard, spoke of “America’s chickens coming home to roost.”

The United States under Joseph Biden has raised its military budget to over $780 billion, more than those of the ten nations next down the row all put together, including Russia and China. But America’s roads and bridges are falling apart. There is no proper health care for millions of Americans. Their public education is a disgrace. America’s infamous 1% is immensely rich, the vast majority of Americans are battling to survive. Experts tell us that 1% of America’s military budget can secure fresh, drinking water for the rest of the world. One, no matter how rich, cannot maintain 800 military bases across the world, be involved in wars against seven countries at one time, have regimes of sanctions against over thirty countries as we speak, and tell one’s people that they are “prosperous”, or, in the words of Nelson Mandela, “a nation at peace with itself and the world.” A war economy is an economy in slow-motion free fall. When the most eagerly awaited and most frequently question asked is, “Who do we go up against next?” and not, “How can we give all our children a better future?”, or “Can we solve the problem of homelessness?”, that is a country in serious decline.

But the decline is not only economic. There is, the true prophets of God in America keep on warning their people, also the political and moral decline to take into account, and to account for. Despite the never-ending wars, or perhaps because of it, seeing the need for the creation of equally never-ending waves of fear, America is not a “secure” people. Its democracy, despite the screaming propaganda, is not only in decline. According to a recent study by scholars from Princeton and North Western Universities, democracy in the United States is at best “accidental” and at worst an oligarchy. Its laws are written by what they call lobbyists, who bribe and buy votes with gay abandon in Congress, only Americans don’t call that “corruption”, as they should, because it is legal. “Come back when you have money!” is the telling caption under the picture of the crowds protesting at the Capitol accompanying the study.

Never-ending wars need never-ending, ever newly created enemies. That, in turn, needs the constant, and unbridled demonization of others, at the moment not so much the Muslims, but the Russians instead (though I am sure that Yeminis and Sudanese will disagree). We know the hatred will return in full force once the hysteria about Russia and Ukraine comes to an end, for that peculiar appetite, once whetted, has to be satisfied. Waiting their turn in the background are the Chinese.

In America, I have seen, creating enemies is an industry, and an extremely profitable one at that. Making profits out of self-made disasters and cultivated needs is the lifeblood of neoliberal capitalism. The mass media have developed it into something of an art. In the six years my family had lived there, and I had taught there, I watched in awe as this phenomenon played itself out on television, and with a gusto that is beyond belief. Watching this on television from somewhere else is one thing. Up close and personal is quite another. That does not make for a secure people however. They cannot be secure because they have to constantly lie to themselves – about others, about the world, and about themselves. The language of war and aggression, of lies, deceit and demonization is incapable of forming the grammar of peace and security.

The people of Laish “possessed wealth”, but the city was peaceful, for its people felt secure, which in the context of the times speaks to a system where wealth was more evenly distributed, lessening, even preventing, the tensions in society that vast and unsustainable inequalities bring, promoting a sense of common wellbeing. They were “unsuspecting” not because they were a naïve and stupid people, but because they were not a war-like people. Their desire was not for wars and conquests, it was to live in peace with others as much as possible. Peace with others means peaceful trade with others – of those olives, figs, and wine they have time to cultivate and nurture to perfection. Somehow, the people of Laish had found a formula that defied the times.

When the fire of hatred is in our hearts, the words of peace, when we finally find them to speak about our favourite causes, burn the roofs of our mouths and scorch our tongues so the words come out twisted, and unreal, as with the selective indignation over Ukraine, so painfully apparent over the few past weeks as I have been writing this. Shocked perhaps, but not at all surprised, we heard from the mouths of one Western journalist after the other the racist sympathies for people who are “white”, and “Christian”; not Syrians or Africans, but people “like us”, from white, European, “civilised” countries. But those whose hearts are pure in these matters know this to be true: those who cannot weep for Palestinians and Yemenis and Iraqis, cannot weep for Ukrainians. Those tears are like molten lava running over the soul.

But the scary analogies with the modern State of Israel continue. For the unsuspecting people of Laish, like for the Palestinians, the text says, in a seemingly throw away sentence, “there was no deliverer” (18:28). Indeed. No Western country, even while watching the land theft, the murder and mayhem visited upon the Palestinians, come to their aid. They don’t have the shame to even look away, for they watch with their eye keenly on the next opportunity to present the Palestinians with one more “peace plan,” yet another “road map to peace”, which they draw up so that all roads lead to more pacification, more Israeli impunity, more dispossession. They watch the growth of Israeli settler communities on stolen Palestinian land, the “legalisation” of the Israeli apartheid state, the expansion of the Israeli settler colony, and they do not find that in the least obscene, or objectionable, beyond a few pious words accompanying the wringing of hands that have no meaning and no intention of justice. It’s all permissible, because the Palestinians are doomed to pay the price for centuries of Western anti-Semitism and Western guilt. This is where white privilege and white exceptionalism ultimately take us, always stoked, always protected, and always justified by the heresies of Christian Zionism.

Not so long ago, I was in a rather tense Zoom discussion with theologians from Europe. A German colleague, high representative of the German Church, explained how his heart melted in sympathy when, on a trip to the Holy Land, he saw what Palestinians were going through. But then, he said, I go over to my Jewish hosts and I think of what we have done to them, and all I can do is ask my Palestinian friends to “build that bridge and make peace.” Note the wording though: he looks at the Jews and when he remembers what Germans have done to the Jews, his heart melts again, but this time with guilt. So in Germany, and Europe in general, they actually pretend they can wash the guilt of their past off their hands with the blood of Palestinians, and still find favour with God, make peace in the world, and hold onto their innocence. Note also how he shifts the responsibility for peace from the powerful to the powerless. As if the Zionist regime is always ready for peace, but the savage Palestinians are not, so it is they who must “build that bridge”. For Christians, that should be a horror of heretical proportions. That is what I thought and that is what I said.

European, American, and South African Christian Zionists, in the name of Jesus, and under orders from the American empire, crucify Palestinians on a daily basis as they once did Jesus, the One from occupied Galilee in occupied Palestine. Today they compound the pain of Palestinians, and their crimes against the Palestinians, with the unbelievable hypocrisy we are seeing with the war between Ukraine, backed by the US and NATO, and Russia. No constant howls of indignation for Palestine; no saturation of news 24/7, calling for sympathy and solidarity, not even a whiff of recognition that what is happening is wrong, even though they all know that what Israel is doing is a crime against humanity. Now they know perfectly what a war crime is.

And the hypocrisy screams to the heavens. I watched, amazed, as Condoleezza Rice, National Security Advisor for George Bush, deeply involved in the deceptions about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and in the lies they told to the American people and the world, a war criminal, in other words, like George Bush, Dick Chaney and Tony Blair, spoke without the slightest sign of discomfort about Putin. How he should be hauled before the International Criminal Court, as if she herself, and all her colleagues did not belong there together with Putin. As if the US itself had not refused to join the ICC, and had not promulgated an act that allowed it to invade The Hague should it dare to charge any American with a war crime. And most disturbing of all, her American television interviewer sat there, allowing her to pontificate unhindered, as if all this was not worth a single challenge or correction.

The sanctions against Russia are gushing out like water from a broken pipe. What, for over twenty years, we were told was impossible and impractical (because it was Israel), is now suddenly possible, and practical; and worse, the right and moral thing to do. Those impossible sanctions are announced, and implemented, overnight. We argued endlessly in the 1980s that taking such a firm, nonviolent stand against apartheid was in actual fact the indicator, if not the litmus test, for the morality of politics and for the integrity of Christian witness. I vividly remember not only the vacuous arguments, but also the deeply emotional reactions.

Again and again, I have made the argument that that same situation pertains to the question of Palestine and the call for boycott, disinvestment and sanctions. There were all kinds of quasi-theological arguments, skewed, and highly hypocritical, biblical references to “love”, “reconciliation”, and “patience”. Now, all of a sudden, that moral standard exists, and it is Russia. It is an ideologised theology that fits the crime. They act if the deepest motivation is not the profits that are being made by stoking the war; as if the reality is not, as Democratic Representative Adam Schiff blandly admitted on December 22, 2020, “We must fight Russia over there in Ukraine so we don’t have to fight Russia over here.” In other words, America must get the Ukrainians to fight Russia till the last drop of Ukrainian blood.

Like the Danites, after the slaughter of the people of Laish, “set up an idol for themselves” (v.30), the Americans and Europeans are eagerly building altars for their idols of war and false gods of capitalism. But the sacrifice on those altars are the children, the women, and the grandmothers of Ukraine they parade so piously, and shamelessly, on their television screens. The sanctimonious, hateful, spiteful glee is almost worse than the hypocrisy. But as the writer of this part of Judges points out in the subtle mention of the idols the Danites now pay fealty to: they need those idols and false gods, because God has long departed.

III

The tragedy in Judges is that the violence that Israel embraced so eagerly in the first chapters of this book, runs its destructive path right through the book and, in the end, right through the heart of Israel itself, tearing it apart. Violence does not only beget violence, Judges is saying, violence is a horror that, once loosed, cannot be controlled or steered into the precise, but entirely imaginary paths we have plotted in our minds and our theories so completely detached from reality.

Andrew Bacevic is a respected American academic, one of the sane voices to listen to when it comes to America’s wars, and in the case of this current US/NATO/European war, one of the very few. A retired colonel in the American armed forces, he was once a commander in the war on Iraq. I learnt much from him about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, why so much has gone so wrong. His colleague, General Frankie Thomas coined a most memorable phrase about the Iraq war: “America’s catastrophic success” he called it.

On Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now! I listened to Andrew Bacevic, and even he sometimes get tripped up in the propagandistic tsunami Western media have become. He allowed Amy Goodman to trap him with a request to speak about the “particular brutality” of Russia’s war against Ukraine, and he did, for quite some time. He is not wrong. What is going on is a serious breach of international law, and there probably are war crimes being committed with every new onslaught. President Putin knows it. But then, taking me a bit by surprise, he gave the reason for “Russia’s brutality”. The war might have been thrust upon Russia by NATO’s irresponsible urges for expansion, however, Russia, he says, should have known better how to use “controlled violence.” Any modern army should have that capacity, Bacevic argues. “Controlled violence” in a war is how “professional armies” do their business.

Let us make no mistake, that war in Ukraine is brutal. But what war isn’t? Why do we allow ourselves to think of one war as “less” or “more” brutal than the other? Every war, without exception, is unspeakably brutal. The weapons now deployed are weapons made for total destruction. One painful lesson from the Vietnam war, and the never-ending wars of the last thirty years is, there is no such thing as “precise” targeting, or “surgical strikes.” We now know of the hundreds of drone strikes that were supposed to be “targeted,” but ended up striking schools and hospitals, killing children on the playground, civilians in the streets, and couples and their family and friends at wedding parties. That is why our theological insistence on looking at the world and our realities through the eyes of those who suffer, the victims, and the excluded, is so crucial. And why is the brutality of the war in Ukraine such a hot topic of discussion, when the brutality of the war in Yemen, and the US naval blockade of that impoverished country, for example, never was, and still is not worth a mention in Western media?

Andrew Bacevic knows that too, and tells us so, when he finally did come to acknowledge that Americans have nothing to crow about and very little reason to shout indignantly at Russia. Recalling the devastation wreaked upon Iraq in America’s “shock and awe” war strategies in Iraq and Afghanistan, “Americans ought to a bit more humble”, he says. I am not really one for splitting hairs, but that American humility really needs to be much more than just “a bit.” The wars against Iraq and Afghanistan wrought terrible destruction: of infrastructure, of water supplies, of oil fields, of civilians, almost 1 million by last count. I shall not even speak of the destruction of a civilization thousands of years old, and of the treasures that Americans stole from those ruins to sell at home to others. The wars against Yemen, Sudan, and other African countries are no less so.

Why is there this constant self-deception and foolishness about war and violence – that we can control it once we unleash it, that we can determine that its path to the “targets” is always true and straight? That we can control the power of violence over the minds of those who use it, how much they come to love it, become enslaved to it, how ultimately they come to worship it? Have we not seen how quickly the violence we think we can use as a “tool” becomes a god we cannot live without? To say nothing of how it makes us feel and act like gods ourselves once we taste the power of snuffing out a human life, whether from a metre away and chopping off a head, or from thousands of miles away pressing a button on a computer?

How quickly did the carefully chosen words about violence George Bush spoke so fervently, and religiously in America’s post-9/11 evangelistic fervour, (remember the “crusade”?) turn into the violence of violence in Abu Graib and Guantanamo Bay prison, but not before turning those soldiers and torturers into the monsters Bush and the American media painted the Iraqis to be. But as surely, however: how soon did the words of our war songs beset, and turn, and poison the minds of our young people who invented the “necklace” as supreme form of punishment of informers for apartheid? Did we ever stop to wonder about our fiery rhetoric about “rivers of blood” as we saw them shedding their innocence forever while dancing around bodies burning to death in flames churned up by petrol poured by young black hands on other black bodies? Freedom songs turned into war songs turned into death songs?

Day by day, all of this strengthens my resolve to stand up against war and every form of violence, and for peace; to shout the message of the Book of Judges from the rooftops. There is no end to the lessons South Africa, and the world, can learn from this book.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.