By Carol Harston

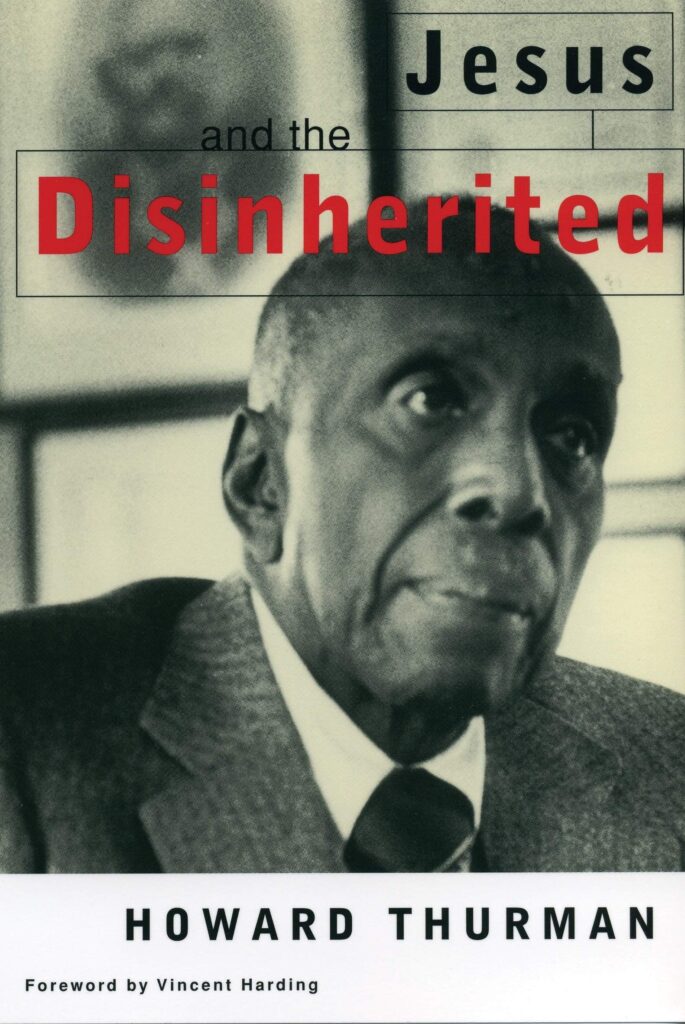

Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited caught my attention years ago. Thurman brilliantly describes the complex and powerful way that beliefs function within the lives of those whose backs are against the wall. Oppressive systems, whether in Jesus’ day or the present, employ beliefs that keep people with their backs against the wall even if the weapons are not exposed.

Thurman’s theology comes to life through his complete, devastating sincerity about life as it is, with Jesus, whose own back was against the wall, at the center.

Thurman locates the birthplace of concrete action as the internal landscape. Only through understanding, recognizing and destroying the fear, deception and hatred of oppressive systems can courage and love via nonviolent resistance be possible. As a pastor and scholar, Thurman knew that religious life was not just about loving Jesus. The spiritual life is about investigating our chosen beliefs and those that have snuck their way into our souls unaware.

Beliefs don’t just dwell in our intellect; they function in our lives. Beliefs are less an intellectual assent or some words we mutter and then shelve somewhere within us. Beliefs exist within us, active and powerful. We don’t only hold beliefs; they hold us.

Some beliefs we choose, while others have been passed down to us. The most dangerous of all beliefs are the ones I don’t “believe” in, but are shaping my words, deeds, relationships and citizenry without my conscious consent or awareness. Beliefs received can soak into our bones, warp our minds, and stunt our development, especially when they reach us in childhood.

The beliefs we don’t “believe” can affect us in sinister ways. The political, social and religious systems that have raised us implant beliefs that function in our internal landscape.

As a white woman of privilege reading Thurman, I’ve lived with the lingering question: What about Jesus and the “Inherited”? For those of us whose ancestors pushed the disinherited up against the wall or lived as silent benefactors of such violent systems, how are our spirits impacted by its legacy and its present evils?

As a white woman of privilege reading Thurman, I’ve lived with the lingering question: What about Jesus and the “Inherited”? For those of us whose ancestors pushed the disinherited up against the wall or lived as silent benefactors of such violent systems, how are our spirits impacted by its legacy and its present evils?

Violence squeezes the disinherited into tight spaces where they must fight for survival. The inherited assume that their wide-open spaces benefit them, unaware of how the evil beliefs born of white supremacy and racial oppression make it so that no one is free. Fear, deception and hatred fuel the whole system; levels must be regularly stoked within the inherited to keep tight the reins, tension racing through the system and wrecking the inherited’s political parties, churches, neighborhoods, family systems and bodies.

Without the system and its supporting narratives, the inherited have much to lose; so they grow up learning that self-protection is not only a “right” but a requirement.

Imagine a house whose rooms have no light. Daylight never reaches inside, and the lights don’t work. The man who lives there finds the darkness scary and unsettling; but his parents brought him up in this house, so it is the only house he knows. He inherited it from them and is proud of his childhood home.

Stories from the generations that preceded him taught him to beware of robbers who would take advantage of the darkness. Beware animals looking for food. Always be ready, weapons in hand, to defend your house from whatever lurks in the darkness. Even as the weapons weigh on him, clunky and awkward at times, they have become so ordinary that he barely notices them anymore.

Then comes a miracle from God: One day, the house becomes filled with light. The dark paper over the windows has fallen, so sunlight streams in. Electricity returns so lightbulbs can shine bright. The man is overjoyed. He can now clearly see all that he has missed. He sees all that he possesses, and he is pleased. Even more importantly, the danger he’s lived with all his life is gone. He can see no threats present, and he will be able to see any danger should it emerge.

Yet, his hands are so used to holding the weapons. He is reluctant to lay them down. Even as he sees all the treasures in his home that he wishes to pick up, examine, hold and admire, he can’t manage to part with his self-protection.

Now, he doesn’t need the weapons to protect himself. Strangely, he still feels the need to protect the weapons from becoming obsolete or, worse, a symbol of his ignorance for all those years in the dark. Understanding is beginning to dawn. But is he willing to see that his eyes will only detect threats unless he’s willing to set down the weapons? With the lights on, can he see in the mirror that he is his own enemy? He is the greatest danger.

Complete, devastating sincerity requires the inherited to realize that the weapons in one’s hands that one has assumed to be self-protection are not protecting anyone. Weapons and wealth wound both the disinherited and the inherited.

When one’s worth is so tied to power, to lay down the vestiges of power can be a terrifying ask. Especially when the inherited have lived under the illusion that one’s sense of self and hope mirrors one’s power and control. The strong are fooling themselves. Beliefs about protection, possession and power cannot co-exist with love and freedom.

When the inherited build more barns to hold their growing empire, fear of losing it all grows. One assumes those without barns must envy great wealth, so one builds another barn just to store the equipment to protect the other barns.

Children of the inherited learn that to be safe, loved and to belong, one must be better than everyone else. One’s value, purpose and place are gained by achieving superiority and lauding it over those who are inferior. If one struggles to be better than one’s peers, the disinherited fill that role. The vast conspiracy of noise drowns out the disinherited’s cries for dignity, resources and freedom.

Are not today’s political landscape and social media newsfeeds evidence enough that contact without fellowship and unsympathetic understanding leave everyone feeling their back is against the wall, even if they’re the ones whose hands hold weapons of power and status? If the inherited think themselves disinherited, what more crucial of a time is it for Thurman’s voice to emerge and guide us to Jesus and his ethic of love-ethic?

Jesus illuminates the house, and the man sees that the only thing to fear is his fear, which has turned everyone into an enemy, including himself.

“In Jesus’ insistence that we should forgive seventy times seven, there seems to be the assumption that forgiveness is mandatory for three reasons. First, God forgives us again and again for what we do intentionally and unintentionally. There is present an element that is contingent upon our attitude. Forgiveness beyond this is interpreted as the work of divine grace. Second, no evil deed represents the full intent of the doer. Third, the evildoer does not go unpunished” (98).

So, who am I?” Jesus leads each individual to ask of themselves. With Thurman’s guidance, he learns to answer “a child of God” and believe it. Considering such grace, he is beginning to see the beliefs once cherished have been the danger all along.

He looks around the house, now full of light, and lays down his weapons. His journey toward true freedom, love, and holy resistance has begun.

— Carol Harston is an ordained minister, wife, and mother. She has degrees from Wake Forest, Louisville Presbyterian Seminary, and Duke University (D.Min.) where she wrote Traumatizing Theology and the Healing Church.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Recent Posts

- The Body of Christ, the Family of God and the Border: Christian Responses to the Immigration Crisis

- When Churches Are No Longer Sanctuaries: An Immigrant Theologian-Pastor’s Reflection

- Risk is the Cost of Following Jesus

- About This ‘Special Issue of CET’

- The Real Scapegoats, According to Matthew and Girard