The War in Yemen: Why it Matters

By Ken Sehested

The news was easy to miss. I saw it in several me- dia, but never “above the fold” or in the opening lineup of topics for cable news shows. And there is reason to debate how significant the news is, depend- ing on your level of political optimism or pessimism.

But the fact that Congress recently voted to exercise its never-before-used War Powers Act to cut off US funding for the Saudi-led war in Yemen is at least unusual. The fact that both the House and the Senate approved the measure is significant, though the margin in the Senate makes it unlikely they can override an anticipated veto by President Trump.1

Created in 1973, after the disclosure of a mountain of governmental lies deployed to sustain the war in Vietnam, the Act was supposed to return to Congress the constitutional mandate for declaring war. The Act has gathered dust ever since, despite the fact that the US has undertaken military action in at least 14 countries since then, including the war in Afghanistan, which has now lasted nearly as long as all our other wars combined.

The devastation in Yemen is hard to conceive: It is too far away (for us in the West), geographically and emotionally; there are multiple actors involved and a longer history to be accounted; and the US role in the war is largely hidden under layers subcontractors (which is the way empires prefer to exert their power, to maintain plausible deniability when espoused human rights values collide with acts of naked aggression).

The most immediate cause of the war goes back to the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings that changed political landscapes in multiple Arab countries.

In this case, the minority Houthi people, devotees of the Zaydi branch of Shi’a Islam who live mostly in the country’s northern region (along its border with Saudi Arabia), began an uprising against the country’s repressive government. The rebellion was so successful—in part because of support from Iran’s Shi’a government—that in 2015, Saudi Arabia, Iran’s principal rival in the region, organized a coalition of other Arab governments to fight the Houthi-led anti-government forces.

One of the supreme ironies in this bloody mess is the fact that, indirectly, the US is funding al-Qaeda, against whom we started the War on Terror following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. That organization’s branch on the Saudi Peninsula is also fighting the anti-government forces in Yemen.

“Elements of the US military are clearly aware that much of what the US is doing in Yemen is aiding al- Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and there is much angst about that,” said Michael Horton, a fellow at the Jamestown Foundation.”2

All parties to the conflict have likely committed war crimes, though in proportion to the very unequal size of their forces.

The war in Yemen, which multiple international authorities describe as currently the worst humanitarian disaster in the world, has caused untold suffering.

The war in Yemen, which multiple international authorities describe as currently the worst humanitarian disaster in the world, has caused untold suffering.

The war is directly responsible for the deaths of somewhere between 15,000-60,000 people since 2015. It’s hard to get reliable information in an active war zone, in one of the poorest nations on the earth.

An estimated 85,000 children have died from starvation and easily preventable diseases; another 1.8 million under the age of five are suffering acute malnutrition. A cholera outbreak has affected over a million people. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, if the population of Yemen were represented as 100 individuals, 80 need aid to survive, 60 have little to eat, 58 have no access to clean water, 52 have no health care provision, and 11 are severely malnourished. To get a sense of the scale of this disaster, project those percentages onto a country of 27 million.

The US role in the war has been substantial and includes accelerated sale of weapons, intelligence, logistical support, aerial refueling of Saudi (and their allies) aircraft, and assistance with targeting.

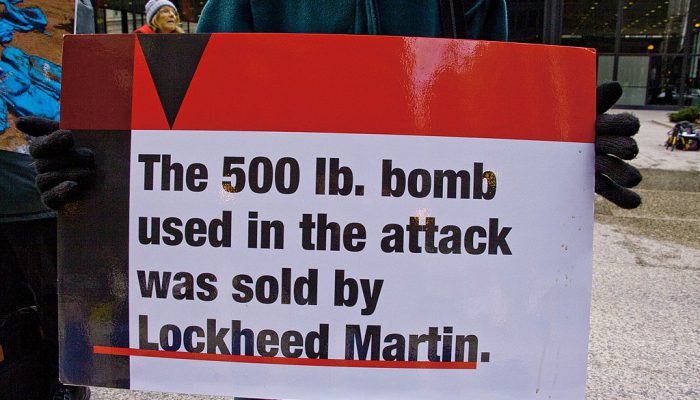

The most tangible link between US arms and civilian deaths in Yemen came when a CNN photographer found a piece of debris with US markings following the 9 August 2018 bombing of a school bus which killed 40 children, 11 adults and injured scores more. It was a 500 pound MK 82 laser-guided bomb made by Lockheed Martin. Note: It was laser-guided bomb, acclaimed for its precision, not an unfortunate act of “collateral damage.”

“The US is completely complicit,” said Kathy Kelly, co-coordinator of Voices for Creative Nonviolence. “It’s like a drive-by. You know, if a drive-by shooter has obtained the car and the fuel and the bullets and the map and the surveillance and funding from another entity, then isn’t that other entity pretty complicit? And if the United States cut all that off, it would bring the war to an end within a day.”3

“And at a flight operations room in the capital, Riyadh, Saudi commanders sit near American military officials who provide intelligence and tactical advice.

“‘In the end, we concluded that [the Saudis] were just not willing to listen,’ said Tom Malinowski, a for- mer assistant secretary of state and a new member of Congress from New Jersey. ‘They were given specific coordinates of targets that should not be struck and they continued to strike them. That struck me as a willful disregard of advice they were getting.’”4

The US did stop aerial refueling last November, due in large part to the public relations embarrassment in the aftermath of the killing of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. President Trump, who publicly celebrated the jobs created in the US by Saudi Arabia’s arms purchases, has contradicted his own intelligence services who confirm that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman directly ordered Khashoggi’s murder and dismemberment in the Saudi embassy in Istanbul, Turkey.

It is painful to admit that the death of one well- known individual has a greater affect on public policy than the death and suffering of millions. This admission underscores the cruel observation of Joseph Stalin, former mass murdering premier of the Soviet Union, who quipped, “The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic.”

To be sure, to fully explore the causation of the war in Yemen requires a longer historical lens. Support for the Saudi-led war was originally supported by President Obama, though Trump has knocked over a number of the guard rails previously in place to reduce the carnage. And remember, Obama’s authorization of 500-plus drone strikes, some in Yemen, far and away exceeded those authorized by his predecessor, George W. Bush.

Drone strikes stretch the distance between predator and prey, making it more palatable for the former to act without regret. The increasingly sophisticated technology of war creates a new moral compass: The further from the actual blood, the easier to sustain being unburdened by ethical qualms.

An even longer view of the war in Yemen goes back more than a century, when in 1916 Britain and France literally drew the current boundaries in the Middle East, abruptly severing historical kinships based on tribal, religious and familial ties. It was a World War I military tactic, whereby Arab leaders were promised independence if they would revolt against their Ottoman Empire rulers.

Moreover, to understand much of the conflict in the Middle East, including Yemen, requires attention to the repressive rule of Arab monarchs themselves, who often made self-interested deals with colonial powers for the extraction of natural resources, oil in particular. It is this corruption that provides a key motivating factor to the rise of revolutionary groups like al-Qaeda (whose jihadist heirs were financed by the US in places like Soviet-occupied Afghanistan) and the Islamic State (which spawned out of the bloodletting and chaos caused by the US invasion of Iraq).

The increasingly sophisticated technology of war creates a new moral compass: The further from the actual blood, the easier to sustain being unburdened by ethical qualms.

Though it likely wasn’t intended, a recent “Garfield” the cat cartoon by Jim Davis brilliantly summarizes the history of Western nations’ colonial foreign policy in three frames.

Garfield, thinking to himself, first says “I’ve decided to give back to the world.” Then, “But first . . . I’m going to take a bunch of stuff.”

“Since 1980,” writes Jeff Faux, “we have invaded, occupied and/or bombed at least 14 different Muslim countries. After the sacrifice of thousands of American lives and trillions of dollars, the region is now a cauldron of death and destruction. Yet, we persist, with no end in sight. As former Air Force General Charles F. Wald told the Washington Post, “We’re not going to see an end to this in our lifetime. . . .”

The rationale here is embarrassingly circular—we must remain in the Middle East to protect against terrorists who hate America because we are in the Middle East.”5

When it comes to foreign affairs (in particular), most do not realize that, more often than not, our nation’s economic interests eclipse our humane political values. It’s not that there are no charitable impulses to be recognized and applauded. They are surely there. But typically these are preceded or displaced or overruled by errant, even vicious self-interest.

I am aware of how frustrating it is to call attention to such tragedies while offering little that can be done in response (e.g., charitable giving to relief organizations, contacting legislators, etc.). It is at least as bad for writers to pile on guilt as it is for readers to remain indifferent. Guilt is not the issue; in fact, it is a dodge. At least in the common meaning of that word, guilt merely assuages responsibility; it does not unleash the freedom needed to make alternate choices and demand different public policies.

Odd as it may sound, the incitement to such freedom is the intention of Lenten observance in the Christian community. Lent’s invitation is to pay close attention, even when it’s discomforting; to strip away the accretions of self-possessed living; to encourage penitential denouncement of miserly habits to make space for regenerate, neighborly response in the midst of history’s degenerate affairs.

Lent reminds us that sometimes a no must be said before yes can be uttered. A kind of dying must occur before the living—for which we were made—can be undertaken.

Before Easter’s resurrectionary profession can be made, a certain insurrectionary practice must be launched. To be enlisted in such a movement is not the achievement of valiant willfulness or moral heroism. Such virtues are noteworthy; but first we must fall in love, to be captivated by what Dr. King referred to as the “Beloved Community,” enraptured by a beatific vision, to the dream of Creation’s purpose and Re-creation’s promise.

These can be accessed only by paying close, risky attention to the underside of history; to the forgotten places, to the overlooked tragedies, to the frail, the frightened, the vulnerable, which call us to compassionate proximity.

That’s why Yemen matters. It is a mirror reflecting who we are; but also a reminder of Whom, and by Whom, we are invited to accompany.

— Ken Sehested is the curator of prayerandpolitiks.org, an online journal at the intersection of spiritual formation and prophetic action.

For more background on the war in Yemen, see: http://www.prayerandpolitiks.org/signs-of-the- times/2019/04/11/news-views-notes-and-quotes.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.